We cross the Canadian border during the 4th of July weekend into farm and windmill country and arrive at Victoria’s sheep farm in St. Agatha, southwestern Ontario. Victoria awaits us down a wooded drive with a couple of Border Collies heeled at her side. Later we will meet Viki Kidd, her lifelong friend and partner in herding and dog training. Her partner in life, John Straube, will fix us dinner. Right now we hear him doing something with the throttle of a tractor.

A lot of us in the Western Literature Association have heard Victoria talk about sheep and dogs and farm life. But to see it in person is cause for celebration. The place feels tucked away in pastoral calm, a surprise given we are close, under 10 kilometers, to University of Waterloo, Victoria’s home institution. Known as the “MIT of Canada,” the University has a huge census of some 40,000 students, but the bustle of university activity seems far away. For Victoria’s bio, see here.

The 1500 mile stretch to get to St. Agatha from Pueblo is the longest we’ve traveled to do a single interview. José wanted to make the drive, he loves the ambition of it and of finding his friend and fellow scholar of 19th century studies on the other side, across the border. Who knew how much Detroit was a border town?!

It’s noon when we park the van, and by the time we leave it’s close to midnight and we’ve talked with Victoria, Viki and John over a long dinner. Farm life, sheep, and the fragility of democracy, what else for the Americans on 4th of July but Canadian outrage about Trump! Victoria’s niece Megan is an athlete staying at the house while her dodgeball team practices nearby for the world championship to be held in Edmonton later that summer. Ellie has gone to practice but her boyfriend, also a dodgeball player, joins us at the table though he is on a training diet and leaves most the food for us. Before the talk gets animated, he has excused himself to do a bit of yoga in advance of practice.

Earlier in the day, Victoria is showing us around. A roomy farm house spreads out, dogs frisky to have us there but they do just as Victoria tells them, the benefits of being a dog trainer. The living area doors open onto a big wooden deck with tables and chairs and flowers in pots bringing color.

The barn house is straight ahead. A “bank barn,” its design is traditional to farmers in the area who excavate what they dig out or muck from the barn floor and create a little driveway from it to the side so machinery can be driven up and into the second floor. They are stored up there with the huge rolled hay bales for wintering sheep.

Beyond the barn lies open land to a wooded backdrop and on the other side of the trees is a running stream. It ties into the Grand River, a major green, clear water river.

Walking out into the open land we see patches of greenspace and Victoria tells us about Bobolinks, an endangered bird species that nest in the chest high grasses. The males are black with white streaked backs, they nest in the spring. Farming methods today cut hay early, which destroys nests. Victoria’s attitudes toward haying have been radically changed by seeing the slaughter of the nesting birds. After haying she saw nothing but birds of prey, scavenger birds coming in for whatever eggs or fledglings could be found.

The farm space is affected by all kinds of global processes, and even if it’s in just a small way, she tries to make it a habitat for birds, threatened species, and for animals that need a place to live. On your own land, it’s possible to have agency, do something.

To protect the Bobolink, she scouts where they nest and marks off areas safe from haying – refuges. There are several pair this season and they chatter as we get near, making an “R2D2” sound and flying away from the nest, to distract us from the fledglings. Each year Bobolink return to the farm, though not to the same patches of grass. Seasonally Victoria figures out anew where they nest to create refuge.

So much to share about this piece of land, and seeing Victoria work the dogs with the sheep. The white dogs, Maremma, stay with them year round, protection from coyotes. We are surrounded by panting dogs, all of them doing their jobs, Elly is the exception, her job is to get up on Victoria’s lap and snuggle.

The Where of Here

Krista

For the last hour we have been talking about the where of here. The sheep, and dogs, and various grasses. There is so much birdsong here! What else might you want to tell us about the where of here, you’ve been here 10 years?

Victoria

I’ve lived here since 2008. It’s a hundred-and-forty-seven-acres of farmland just outside of Waterloo. We are situated in some of the best farmland in the world. I’ve been fortunate to travel a lot. I’ve seen a lot of farmland in Europe. And we’re lucky to be close to this incredibly fertile, beautiful farmland.

We had an opportunity to buy this farm in 2008. At that time, it was cash crops. And the house had been let go, in pretty bad shape. We’ve fixed up the house and shifted from cash crops to raising grasses, and we planted sheep pasture. We work with a partner who’s also a close friend of mine with extensive knowledge of sheep husbandry, Vicki Kidd. She does most of the work with the sheep but it’s a partnership. She handles the sheep side of things. And my partner John handles the machinery. You saw his little “test house,” where he tests building materials. He’s at Uni too, appointed between architecture and engineering.

I like the gardens and I support Vicki in looking after the sheep. I help with lambing. Vicki breeds about 50 ewes a year, and lambs them in February and March. I take night shifts, to make sure that the lambs arrive safely, give help them out if there needs to be intervention. That’s one perspective of where we are.

Krista

Do you want to offer others?

Victoria

There is more, yes, we are a habitat for a lot of different creatures. I’m really conscious of that. There’s a lot of life here. When I talk about “ownership,” I understand that that is a privilege. And it’s a construct, it is luck, not entitlement. I’m conscious of supporting the life that’s here. Deer, coyotes, rodents, there’s other critters that live here by design. That have always lived here, right? There’s a lot of different birds.

Krista

We can hear the bird song!

Victoria

Yeah, and I’m a bird person. I know most of the bird species that live here. I can name them. We were talking earlier about supporting some habitats for especially the grassland birds, like Meadowlarks and Bobolinks that nest here, which is in conflict with raising hay. We come up with compromises so that those birds still can nest here. So that’s the other perspective of “the where of here” that there’s a lot of different kinds of life that inhabit this space.

We have a colony of barn swallows and their habitat is disappearing because modern barn styles don’t support them. When you drove here from Windsor, you might have noticed little kinds of houses?

José

Yes.

Victoria

Those are supposed to be barn swallow habitat. When you destroy a bird habitat here, since it’s a threatened species, you have to replace it. Whenever a barn is destroyed where swallows are nesting, you have to replace that habitat. But you will never see a barn swallow use those structures. They are completely useless. A barn swallow will not go near them. The little houses make people feel good, but it’s not actually helping.

You saw in our barn a lot of barn swallows flying around, nesting, it’s important to me.

And then a third perspective on “the where of here” is historical and colonial, right, that this is the traditional territory of the Six Nations of the Grand River. Ten miles on either side of the Grand River is called a Haldimand Tract. This land specifically is not on the Haldimand Tract. But that is treaty land and that treaty has not been fulfilled, the university I work on is on that land. There is the perspective, right, that this land was inhabited by Indigenous people for thousands of years before my ancestors came here.

I’m descended from Scottish immigrants who settled here in the 1830s and the 401 Highway, actually goes right through the homestead of Alexander Lamont, my ancestor, and they settled here in the 1830s.

Their homestead, the 401 Highway, was built right through the treaty land. I’ve looked at old maps and figured out where it was. That was an early period of intensive settlement in this area, so there’s, yeah, that whole colonial history that this land is a part of.

Krista

You were raised in Edmonton, in the suburbs of Edmonton in Western Canada and Alberta.

Victoria

The way Canadian settlement worked was the mostly Scottish and Irish and English settlers of what was then Upper Canada had families who also wanted land. As western land was colonized they moved gradually West, acquiring it, right? So my father was born in Manitoba because Alexander Lamont’s descendants eventually made their way to Manitoba. On my mother’s side were Eastern European immigrants, also to central Ontario but more in the early 1900s. They gradually migrated further west until my mother and father ended up in Alberta, bordering on Montana.

Two hundred miles north of the border is Edmonton. That’s where I’m from. I grew up oriented to the outdoors. As a teenager I liked horses. I liked to hang out at farms.

When I finished my PhD, I got a job at Waterloo and this is where I ended up.

Krista

We work in regional studies, place is important to people. And yet, there is a way in which we don’t talk about that that, as such. We don’t talk about how place is important to us personally. We talk about particular places we work on and the significance or the history or the layered-ness of those places. But one of the things that’s been interesting to me is to talk to those of us who have feminist commitments in scholarship about the places that we personally are from or love or feel.

I’d like to hear your thoughts about places you feel you belong or that you don’t belong. Can you talk a little bit about places that you love or feel at home and feel like you belong? Or places you don’t feel like you belong?

Victoria

There is probably no space I feel like I belong in more than this farm. I don’t know how to describe it. But I come out here every morning and I hear the birds and I’m just so happy to be here. I really love this place. That is highly fraught I know, right, because that is the product of settler discourse, telling me that I belong here. Because historically I do not.

Krista

This is the very thing we’re trying to tease apart, the ways in which we love the places that we…

Victoria

That we don’t belong, yeah. [laughs]

Krista

And yet we do belong to them somehow. So please talk a minute about what it’s like in the morning, leaving aside for a minute how much of a fiction it is and the historical overlay that we become so good at talking through. What do you do, do you come out with coffee?

Victoria

Oh yeah, I come out with a coffee. I putter around in the garden. I look at how the plants are doing. I love the progress of the plants. I like growing flowers.

Krista

I can tell.

Victoria

I’m too lazy to be a vegetable gardener.

Krista

But you have a short growing season for vegetables? I would think.

Victoria

Oh no, you can grow a lot here. This is the warmest part of Canada. We have a pretty long growing season and there are also workarounds to stretch it out. But I putter around. I look at the flowers. I listen to the birds. I chart the progress of the birds through different, “oh who’s nesting where?” After there’s a storm, I look around to see if any nests have been dislodged and see if I can intervene.

Here is Will (border collie) barking! (Crawling into Victoria’s lap) Will, Will, Will, Will, Will, Will!

Krista

Hi Will!

Victoria

Oh, Will’s decided that you exist.

Krista

Thank you Will, I’m honored.

Victoria

I’m going to put her in the house because I don’t want her to run around. She’s got an injury.

Will, (putting her in the house) come on honey.

I work out here as long as the weather cooperates. I’ll bring my laptop out here.

Krista

You might email me from here, or email your colleagues?

Victoria

Absolutely. I’m emailing my colleagues. I’m writing, I do a lot of writing here. I wrote a lot of the book that I’m just finishing up right now.

Krista

Have you written about this place?

Victoria

No, I haven’t. I should.

Krista

Would you like to?

Victoria

Uhh, yeah. Yeah, I think I would.

Krista

I mean, we will be writing about this place through this conversation right here.

Victoria

Yeah, yeah. It’s weird. My academic writing is quite disconnected from my everyday life.

Krista

Is it?

Victoria

Yeah, yeah. It feels weird to think about writing about my everyday life. Right? I consider myself a writer but my everyday life doesn’t feel like it’s a subject for my writing. And the book I’ve just written is a biography about someone else’s everyday life!

Krista

About B.M. Bower?

Victoria

Yes, a biography of Bower, so it’s all about her everyday life [laughs]. Like who wants to read about my everyday life? But I haven’t thought about writing about my own … I guess I would like to, yeah, yeah.

Krista

Well, we are starting . . .

Victoria

Yeah, yeah.

Krista

You’ve talked about belonging with all its complications. Are there places you feel you don’t belong?

Victoria

Definitely certain formal administrative places, institutional spaces. It’s highly dependent and some of that is my background, a kind of wrong side of the tracks Alberta, blue collar, thing. Not very many in my family went to university.

I’m from a blended family. So all together there were nine. Two of my brothers have passed away. I have two sisters out west. One of my sisters went to university. Oh, no two of my sisters did.

Krista

You are first gen, first generation to go to college?

Victoria

Yeah, yeah.

So certainly spaces that are associated with authority, I’m not comfortable sitting in the Dean’s office, asking for resources. It doesn’t feel like I belong there. I’ve had more practice at it as a tenured faculty member. It’s not the most powerful position in the world, but it’s a lot more power than a lot of people have. So I’m getting a little bit better at it. But certainly, it’s not my happy place. That’s for sure.

Krista

Well, that’s important to, to know, that you understand your history to be the wrong side of the tracks, blue collar.

Victoria

Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah.

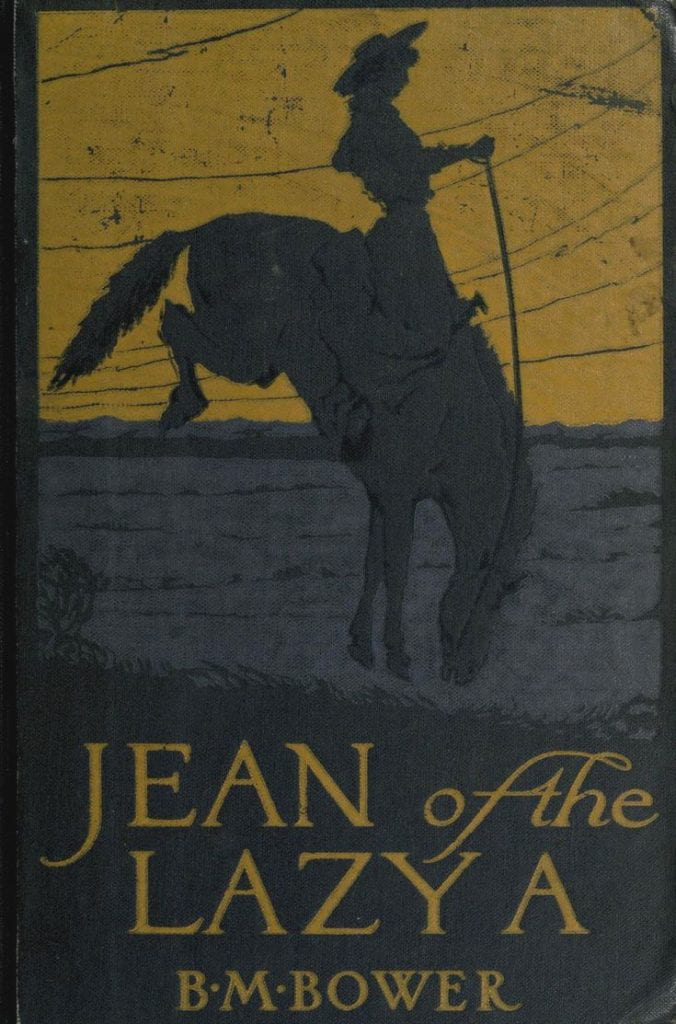

Victoria: “Bower represents feminist wests for me because much of my feminism was shaped in the process of recovering her work along with many other women writers of popular westerns. The image is of my absolute favorite Bower cover design.”

Krista

There’s a couple things at least to think about there. I’ll file that just for a minute, and come back. But since you’ve raised B. M. Bower, and you provided that wonderful visual of the cover of that novel of hers as an example of a “feminist West” visual, maybe we can talk about your own developing feminist perspective?

Victoria

You mean working on Bower? How it shaped me as a feminist?

Krista

Whatever you would like to say about that visual, which has a young woman with a cinched waist and western gear on the back of the horse.

It’s kind of a classic visual.

Victoria

It is classic. It is a classic.

Krista

A pulp novel visual.

Victoria

Yeah, it is. The thing about the sort of popular feminism of that time and even moving forward is that you could express it as long as you didn’t undermine the femininity of the heroine. There had to be a reassurance that she’s still a girl, shaped like a girl.

Reading some of the pulp westerns from the 1920s, the female gunfighter will come on the scene, she’s wearing sort of dirty clothes, and she’s doing something rough, she’s breaking a young horse or something. But there will still be that moment where, “Oh but look at how curvy she is!” Right? Emblematic of the popular feminism of that time.

That’s captured in that image, right? Here she is on this horse, it’s a bucking horse. She’s managing. She’s having fun on this bucking horse.

She’s got a lot of authority, agency. I love the colors of that visual. The vibrancy, evoking a lot of activity. It’s dynamic. When people popularly think about the West as a space that empowers women, that’s the sort of image that they think about. But it’s problematic, right? Because there is that underlying “Oh, but she’s still a woman.” We have to be reassured that oh, the gender categories are maintained.

Krista

So now you are giving the feminist analysis you bring. That’s your… that’s the feminist analysis that you bring.

Victoria

Yes. Yes.

Krista

I am thinking about a number of things from here. Maybe you’ll talk a little bit about how you came to work on Bower? I know you work in the turn of the century, but I’m also mindful of what you are saying about loving creatures and that being part of your feminism. We could call it a kind of eco-feminism if we wanted, but you didn’t call it that, so let’s not. But I’m mindful of all of those things operating and when you talk about the horse right now, and her agency on the horse and being at home on the horse, I wonder how B. M. Bower comes to attract a kind of feminist attention from you?

Victoria

I’m gonna just talk. Because when you asked me to interview for this project I really wanted to do it, but I wasn’t quite sure how to situate myself. I’m different from a lot of the scholars in this field because I don’t come at the West from a place of identification.

Krista

Good, this is perfect.

Victoria

I started to learn, when I started going to WLA regularly, that I came at it as an intellectual. It was, “Look, there’s this woman. She’s writing Westerns. And all the scholars are saying that women didn’t write Westerns, this didn’t happen. So I want to know more. And I started to work on Bower.”

I wasn’t particularly interested in western American literature, per se. I didn’t read a lot of it. I started graduate school and encountered it through [the scholar] Christine Bold and her course. And it raised interesting intellectual questions for me. But then I started going to WLA and a lot of the scholars that I got to know through WLA were coming at it also from this place of identification with the region, which I was not conscious of in myself.

Even though I am, I was born in the West.

Krista

The Canadian West.

Victoria

But maybe unconsciously, there’s a drive that this work is satisfying that my ego just doesn’t want to acknowledge [laughs].

I don’t have that sense of attachment to place that is driving the scholarship that I’m doing. But, then intellectually, “place” became more interesting to me as I learned more about those questions. Also, when I started working on Bower, all I had were her novels. I didn’t know anything about her as a person, or what places those novels were coming out of.

As I learned more about her life story, and I learned about those connections between where she was living and what she was doing, and what she was writing, then questions of place really animated and became more interesting and made the work, made her writing, more interesting. I did start, through this influence of the WLA, to think about like: I am a Westerner. It made me look more critically at my own history, and situate myself in the history that I was learning, that I was studying.

And I became aware of myself as a settler, and as part of settler culture, and how my family and my upbringing was influenced by settler culture in ways that were completely repressed. So there is a circular thing that does come back to thinking about my own situatedness as a Westerner, but that was not something that drove my work initially. I knew I wanted to do Americanist scholarship, but I could have just as easily ended up being a Dickinson scholar, it was such an accidental thing that got me into it.

Krista

I’m thinking about everything you’ve been saying about to Western studies, sort of “by the way.” I’m thinking too about feminist studies, and feminist analysis, and wonder if you want to reflect on how you came to that approach?

One recurrent topic of these interviews is that people didn’t realize impressions of feminism that predate when they actually come of age as feminists, right? The early images predate becoming “aware,” and those early images have an influence on what they either identify or dis-identify with.

Victoria

I don’t know. I mean, certainly a lot of my feminism is a response to growing up with a lot of really toxic misogyny, normalized misogyny, especially, in school which was not fun for me. I realize now that a lot of what happened was just normalized misogyny.

Girls were harassed constantly. And the school system just-

Krista

Including you.

Victoria

Yes, including me.

I decided to become an academic because the space of the university was, it felt so right.

Krista

There was an opening?

Victoria

Yeah, yes, yes. I was smart, right? I was always a smart kid. But in junior high and high school, being smart was not an asset. I think that’s a class thing. So finally, I got to this place where being smart was rewarded and it was valued. But certainly, first 12 years of school were not fun, right. And it those experiences, at a gut level, that’s when I became a feminist. Because living through that was just so traumatic.

Krista

Traumatic?

Victoria

Yes. And so I just feel a deep commitment to dismantling the conditions that put people through that. And it extends to anyone experiencing any kind of socially enabled oppression or exploitation. It extends to all beings, right, who are affected. You can’t stop with sexism, right.

Krista

Right. But your own experience was as a girl. And as a blue collar girl, is your term.

Victoria

Yeah, yes. Definitely. Yeah, yeah. Yeah. I think the way I connect it to blue collar culture is I think that’s where the males feel empowered through the way that they dominate women. I’m not a sociologist, but that is my theory.

Krista

And in your own history?

Victoria

In my own experience, that’s where they got their power. And so the school-

Krista

This would be guys at the school, who were all blue collar guys?

Victoria

Yeah. Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah.

Krista

Is there an example you’d like to share? It doesn’t have to be about you personally, I’m not like hunting for . . .

Victoria

Oh, sure. I’ll give you an example. This would be about seventh grade.

Krista

Puberty of course.

Victoria

Yeah. And there were male students who were assaulting girls, right? They were grabbing their breasts, grabbing their buttocks. And this would happen in the class with a teacher there, right. And there was one girl in particular, she was very tall. And her physical development was advanced for her age, and she was a target. What I heard was a teacher or some teachers took those boys aside who were involved and said to them, “Oh, yeah, we know you want to do it, but you can’t do it.” But they normalized it, they sort of said, “Yeah, of course you-“

Krista

Of course you want to do it.

Victoria

It was that kind of stuff… it happened in classes with authority figures there. The girls were not safe in school at that time. But it was completely accepted. It never occurred to anyone to go and tell their parents, “Hey, did you know that we’re being assaulted?” We didn’t even use the term assault, right? Like we have the language at least now to call that assault. But that’s not what we called it, right?

Krista

What would you have called that kind of thing?

Victoria

We could’ve called it, “Oh, you know, they’re groping or they’re messing around,” something like that. Something that’s much less violent, cleansed of the violence of what they were doing.

Krista

I want to shift gears a little bit, ask if you want to talk about anything we haven’t talked about or ask me something or José something? Or just to direct us in a way you might like to direct it.

Victoria

Have I talked about stuff that you were looking for? You’ve really helped me think about, well, there are the intellectual drives behind your feminist studies, but then there’s the affective, like, why am I feminist?

Krista

Right.

Victoria

And you’ve helped me think about that part of it.

Krista

It seems like part of your feminism was an epistemological and environmental intervention.

Victoria

Yeah. There’s also like, a deeply-felt commitment to things that are wrong with the world that should be exposed.

Krista

A feminism that extends beyond like a woman-centered kind of politics to a broader social justice platform? Including, including animals. You have talked about that.

Victoria

I’m not “an animal studies person.” I’ve learned some things from it but . . .

Krista

But you’re leading an animal studies life here. You talked about riding horses early and birds…

You do sheep midwifery, I’d say that’s a fairly real time “animal studies.”

Victoria

I’ve always been oriented towards animals, whether it was cats or-

Krista

What’s an early memory?

Victoria

Just at home, cats, dogs. If we found an animal and wanted to bring it home, the parents would say okay. [laughs] So we always had dogs and cats at home, and, that sense of power relations, of normalized patriarchy, of people who are enacting it and perpetrating it, you don’t want to reenact that in your relationship with animals. Right?

Krista

You don’t. You don’t.

Victoria

I don’t want to, right. I have to remind myself.

Krista

Because many people, of course, do reenact it.

Victoria

Yeah. You don’t want to objectify animals the way you’ve been objectified. It’s complicated. Some of these animals we have, they’re our property. Right? Like, Elly is my property. But that’s not what she is to me.

Sometimes you still have to make tough decisions. Like I decide when their life ends. And when you’re managing livestock, there’s a practical side to it. Some things that you do with animals because it’s practical are maybe a violation. We remove the sheep tails, because they get certain diseases from flies laying eggs in their tails. When they’re little, when they’re not even 24 hours old, they get a band put on their tail, that cuts off the blood supply. But I’m not going to do it and tell myself that it’s just normal. Right? That it’s just the way it is. Like you are causing suffering to this animal. I don’t know the right words for it.

Krista

There’s an ethical dimension to everything you’re talking about.

Victoria

Yeah. When you’re working with livestock, suffering can happen. Right? But let’s not pretend that it’s not happening, which some farmers, that’s the attitude they take, that it doesn’t exist. Right. But I can’t, I can’t participate in the objectification of another creature and that does not align with my feminism.

Krista

One thing you mentioned that might be interesting to talk about for a minute. You and I have talked about “rural femininity,” and rural gender roles and culture as complicated for a certain kind of feminist performance. You say you choose your battles carefully.

Victoria

Yeah, because this is conservative country. We’re adjacent to a Mennonite community, right, a thriving Mennonite community. We do a lot of business with Mennonites. I go and I shop at the Mennonite store, they have very, they have very different ideas about gender than I do.

There is also just really conservative, agrarian culture, Southern Ontario conservatism. And how productive is it? There are mixed views in our, in my family and John’s family, John’s family tends to be more conservative, they live nearby as dairy farmers, he was raised milking cows. I also have siblings who I don’t agree with politically. And so in some settings, what is going to be accomplished? You have to think.

But on the other hand, there’s “well, what am I doing… I should be causing friction too.” I feel an obligation to create friction. I can tolerate sexism more than I can tolerate racism, I feel like racism is where I have to create more friction, because as a white woman, I have a lot of privilege. I have to leverage my whiteness when the opportunity or when the duty is called upon.

But at the same time how much effect is it going to have? That kind of a negotiation in the different spaces where I circulate… you know, it could be a family gathering in John’s hometown or a faculty meeting, right.

Krista

In the faculty meeting, do you come to that with your rural woman identity as much?

Victoria

Uh that’s interesting. [laughs]

In a faculty meeting, my department is quite progressive. You know, anti-racism is, is normalized, anti-sexism is, is normalized.

So there’s no problem. Oh, well, I shouldn’t say that. Because in some situations around hiring, I have had to say, when we’re creating job descriptions and so on, “This is a recipe for a white person.” Right? Because my department is better than it was, but at one time, it was almost entirely white. I had to push back against that, but in other ways, it’s much easier to articulate feminist positions in that context.

And then there will be a family gathering where there’s the racist uncle, or, the transphobic cousin and I struggle. Do I say, “Okay, I’m not going to go to Christmas dinner because I know you’re going to make some comment that’s going to…”?

Krista

Because it has to be answered.

Victoria

Those are issues that are spatial, right? Because they’re sort of a function of this place where I am, and my profession, which puts me in more of a sort of urban cosmopolitan framework. The faculty are from all over Canada and the United States. Students are from all over. A lot of Middle Eastern students, more and more Black and Latinx students. I’m in a cosmopolitan setting and then . . . but in terms of more my personal life, situated here on a farm, we have our farming friends. Rural Ontario is incredibly white. If you go to any agricultural fair, and fairs are huge in Ontario, especially in the fall, every town has their fair. It will be a sea of white faces everywhere. Then you go to Toronto, and you’re the only white person, you go on the subway, and you’re the only white person on the subway. Right. So it’s incredibly white.

Krista

How’s that for you?

Victoria

Being the only white person on the subway? [laughs]

Krista

No, the other one, being white in a sea of white people.

Victoria

Being in a sea of white people? It’s weird. Growing up, it wasn’t weird. It was just the way it was.

Krista

You were always around white people?

Victoria

Well, no, but Edmonton was very segregated.

And there was a lot of normalized white supremacy. Which I participated in and my family participated in. I had a close friend who actually had to leave because of the racism and when she left, I said, “I don’t understand why you’re leaving.” And she said, “I can’t stand it here. It’s so racist.” And I said, “I don’t know-”

Krista

That was a moment of learning for you.

Victoria

No. I didn’t get it, I had no clue. [laughs] I was so naïve.

Krista

Where was this? Where did it happen?

Victoria

This happened when we went to university together and after we both finished. She was of color and we had known each other since high school. She says, I’ll probably leave this place. And I just did not understand what she was talking about.

Krista

This is after university?

Victoria

Yeah, after we just finished university. So we were 22, something like that.

Krista

Your race consciousness started to develop then?

Victoria

No. It did not. [laughs] I’m ashamed to say.

Krista

Well, you have quite a lot of company.

Victoria

I have to say there was a lot of kicking and screaming before I-

Krista

That’s important.

Victoria

It was as an academic and working in western studies. You can’t call yourself a scholar of this subject matter and not engage with race, you just cannot. I came to that realization when I started really engaging closely with postcolonial theory. My supervisor, Mary Chapman pushed me to read Indigenous authors, and I didn’t want to. I can’t do that, I said, it’s just too thorny. And I didn’t want to deal with it.

This is part of whiteness, you don’t have to deal with things. So I just didn’t see why I would have to deal with it. It was through scholarship, actually. And through teaching, because my students are becoming more and more diverse, and I have to be more accountable to them. When I first started teaching in Waterloo, the student body was very local and very white, but that has changed. So it felt wrong.

True Confessions of a White Scholar.