It’s serendipity that Audrey is in Santa Fe the very same week that we pass through on this summer’s Living West tour. Audrey is doing advance work as the President of WLA in 2022 with her co-President, Lisa Tatonetti. We find Audrey in the gardens of the Georgia O’Keeffe Research Center. It’s Monday, the Center is closed to the public but Audrey has arranged for us to be there in the midst of all else she is doing! You can read Audrey’s full bio here.

Apparently, the gardens will change in the next few years, some of the trees will come down, and Audrey tells us to soak up the grounds as they are while we can. What a beautiful, lush place.

Our conversation is more back-and-forth than some of the others posted to the blog, and I made an editorial call to let stand that character of our exchange. Our discussions of the status of feminism and Audrey’s questions to me about the project became an occasion for me to reflect on where we are, in process. I’m grateful for the chance.

In keeping with Audrey’s sense of place as tied to food cultures and local cuisine, after our time in the Gardens we walk to the Santa Fe Teahouse for a leisurely lunch. She had not been, we had not been, and what food! The Teahouse spreads its pleasures over several split-level dining areas, some indoors, some out. Food, company, tea! I remember Audrey’s burrata, heirloom tomato, and basil salad. For the table we ordered the cold avocado cucumber soup. I took home a warm scone of pear and sliced almonds. José was already happy but then he saw Wes Stude having lunch with a friend and looking, as José said, very much like himself. José’s very good day got better.

Looking back, I am mindful our conversations preceded the Supreme Court “Dobbs” decision in June, which overturned U.S. women’s constitutional right to an abortion. After the leaked draft opinion of Justice Alito, the Women’s March organizers had dubbed it a “Summer of Rage.” In our travels, I certainly felt a sense of fury, anticipatory dread, and also an urgency to advance conversations about feminism in its many guises. That urgency continues to grow.

The Where of Here

Audrey

We are here in the garden of the O’Keeffe Research Center. It is a place that has many layers of complicated history that certainly preceded me but also provided a ground for scholarly exploration, for personal exploration. I picked it because it’s a powerful Indigenous space, Tewa land, the White Shell Water Place originally. That’s not really visible except in the greenery, perhaps, and in the lushness of this environment. I think about this place through Indigenous lands and the range of sovereignties that are not always visible in Santa Fe. At the same time, being here is an opportunity to reflect on those histories, and find places and ways to make lots of stories visible. That’s a process that I’ve been engaged in throughout my work, but especially in this place, and in this building, where I had my favorite, favorite office ever.

It was on the second floor, in the front. I got to come here every day and do my work and think, and come out in this garden. It’s a really generative place for me, in terms of my thinking, in terms of giving me an opportunity to expand my knowledge and to work collaboratively with other scholars.

Krista

Do you have a first memory of knowing about Georgia O’Keeffe? Or beholding her work, having it speak to you?

Audrey

Her landscapes in northern New Mexico, of Abiquiu: I loved always the way that she would paint a place many times. There would be: The Black Place I, The Black Place II, The Black Place III. Apprehending her work over time, and seeing how she found her places, and how her art and her vision led her to pick the places where she wanted to work, was a powerful model for me.

I came here, though, because one of my colleagues, my department chair, had put in my mailbox a notice for Research Center Fellowship applications. He said, “Oh, you should apply for this.” It was while I was still finishing my first book. I wasn’t writing about O’Keeffe in that book. But this Center, under the vision of the previous director, Barbara Lynes, was a place that was supposed to bring together scholars in American modernism. So that gave me an opportunity to come here and think about my work in literature and photography in conversation with not only what O’Keeffe was doing, but with her role as a pioneering modernist, and a pioneering woman in terms of her lived experience in the West.

Krista

She gave you a way to be in the West, yourself?

Audrey

O’Keeffe was a model of how to work in the West and how to create a “vocabulary for “re-visioning place in the U.S. West,” to quote the subtitle of my essay for Routledge’s Gender and the West. And how to live in a place, and develop a relation through everyday observation. How to find the places that, I won’t say she made her own, but that became significant through her representation of them. You see it in the ways that she will look at the interior of a flower, at a city view from one window. She’s an artist who is very conscious of her perspective and the scale in which she works, in how she develops her way of seeing. She continued that practice until the end of her life. She was persistent.

Krista

As someone educated at Columbia, from the East Coast, interested in modernism, how did you come to work on the West? Not that the West belongs to people who are raised in the West because obviously the West travels. I’m thinking of Neil Campbell’s notion of westness and how the West moves and is created at its “outsides” and borders. But for the Living West project we are focusing on place and feminism, and I’m interested in how “the West” began to speak to you.

Audrey

It spoke to me through the writers. My introduction to the West primarily was through novelists and poets and powerful photographers and artists who shared their way of seeing and working through their relations to place in a way that resonated with work that I’d done previously.

When I was a younger student, a college student, I was drawn to feminist poets, to the work of Elizabeth Bishop, and Sylvia Plath, and Marianne Moore, poets who were intensely aware of their own place, and of the language that they wanted to use to claim their identities in relation to lots of different places, who moved around and who were very much itinerant modernists.

Krista

And yet associated with certain places.

Audrey

And associated with their places, in unexpected locations. When I was in graduate school, and I was thinking about really local knowledges, which is an idea that I come back to throughout my work, I was drawn to poets of the early 20th century, but also to writers like Cather, Mary Austin, who really contended with the languages and the feelings of everyday places. Those places were in the West. And these writers were responding at a historical moment of tremendous economic change and cultural change. Their work was responding to and creating a sense of . . . I don’t know. . . it was kind of messy work. But work trying to articulate what it was to be connected to the West, or what it was to be a white woman in this area of the Southwest. We see that in the writings of Austin.

I was interested in their language, and in their process of trying to figure things out, through lots of different forms. Cather’s fiction is complicated for a lot of reasons. Through its effort to work with archival materials, different kinds of family memories, different kinds of environmental histories and to integrate them. It’s also complicated formally, in the way that she composes the different sections and juxtaposes points of view in her fiction. I was interested in Austin’s work for those reasons as well. That seemed different to me than the emerging genre of the popular Western, very narrative driven, but at the same time [a genre that] had all these crazy disruptions and representations of landscape, and all kinds of, you know, gender trouble. Popular Westerns were a lot of fun to work with, too. As I started to explore different genres that were contending with the complexity of western spaces, I started to think about regionality, from a literary point of view, but also as something that is composed, that’s invented, that is problematic. I started to think about regionality generally.

Krista

Of the questions I shared with you for today, are there any that you wanted to answer? [Audrey laughs] Sometimes questions speak to us in a way that . . . they suggest something we’d like to talk about.

Audrey

One question was about where people feel at home.

Krista

Yes, what are “your places,” or “your people’s places.”

Audrey

Right, exactly.

Krista

That can be a trickier question.

Audrey

Well for me, the places are offices and libraries and workspaces. Like this office at the O’Keeffe Center. I loved working in wonderful archives at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, too. For me, being in the archive, then being able to go out and walk in the canyons, like Sabino Canyon outside of Tucson, having read and thought about Almanac of the Dead. Then to go back into the archives. That conversation, one that I am trying to make visible between literary texts and visual texts and archival materials, is something that an archive enables.

Krista

They are workspaces and they’re also spaces in which intellectual women, and of ideas, can be centered.

Audrey

Yes.

Krista

A close friend, Rosemary Hennessy, has just completed a book called In the Company of Radical Women. Written during the COVID lock down. About women writers of the 1930s, and their relations to the Communist Party and to the longer histories of her own Marxist feminist politics. What I am hearing is something I think about a lot which has to do with: how to be a feminist in certain places [like the US West] when feminist ideas might be not associated with the place, or they are strongly disassociated with the place, hard to associate at all with the place. And one of the ways you can make that leap is with the company of other thinkers and writers.

Audrey

Institutions are important too. They’re difficult places, but important feminist work happens there. You can say the Huntington Library, with a very complicated history, colonial history, . . .also gives an opportunity to get to texts, like the manuscript I looked at with all of the notes taken by Charis Wilson when she was with Edward Weston. They were doing their California and the West book. I was able to be in that library, looking at Charis Wilson’s notes of their day-to-day life, what contributions she made, what her transcriptions contributed to that book. Recognizing the value of those institutions, whether they’re universities or libraries’ collections, in terms of places that give space to tell stories about the West, those are really important. The places where I’m at home are in libraries, and in the kind of offices and studies that I’ve created for myself. My favorite study was my house in Albuquerque where I had a beautiful white desk and the windows open and nothing fluttering.

Krista

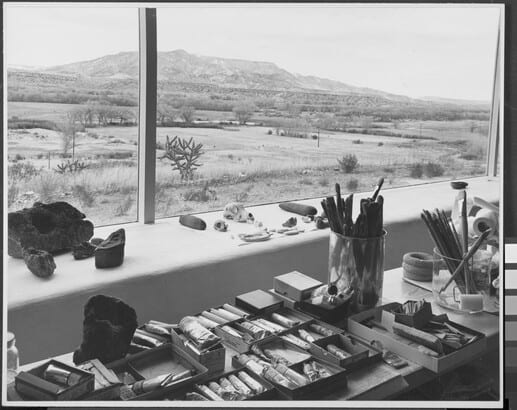

A bit like the visual that you shared of Georgia O’Keeffe’s. A representation of “feminist Wests.”

Laura Gilpin (1891-1979); Studio of Georgia O’Keeffe [New Mexico]; 1960; Gelatin silver print; Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas; Bequest of the Artist; P1979.108.469

Her working space. I’m interested in her vision, but also, what her daily life was like. What created the conditions for her to do that work? Of course, she was privileged to do that work for a lot of reasons. But she also created that.

And then, thinking about other places . . . I love being in and living in Atlanta. Whether in the West or elsewhere, I’ve looked for the places where I feel connected to the local culture and for me, that’s often through taste and food. One of my favorite places is in Albuquerque, Duran Central Pharmacy – have you been there?

Krista

I don’t know if I have.

Audrey

Oh, my goodness,

Krista

Duran’s Central Pharmacy? What would you eat if we were sitting there?

Audrey

Well, I’d eat a bowl of green chile. It’s the purest. I love green chile in all forms, but there it is served in a bowl, and you can get beans in it, you can get chicken. But I don’t need those things.

Krista

All you need is the chile?

Audrey

Just the chile! And then I might have an egg on the side. They make flour tortillas that are bigger than anyone should eat in one sitting but sometimes you can’t help it. [Krista and José laugh] There are women who make the tortillas and you sit at the counter or you sit out in the little patio. I’ve been going to Duran’s since my first visit to New Mexico as a graduate student. Staying at an inn, going to the photo archives at the Museum of New Mexico, carving out a week to do dissertation research. Somehow it always begins at Duran’s: have the green chile, then you can move on and do other things.

Krista

Well green chile is, as you know, a signature food of New Mexico.

Audrey

Yeah. Then being up here in Santa Fe, when I was working at the O’Keeffe and living in Nambé, on the road to Chimayó, every week we had to go to Española, to El Parasol, and have the burrito with either green or red chile, extra chile. If I didn’t get that every week, I was missing out.

Krista

What kind of food did you grow up with?

Audrey

I grew up with lots of different kinds of food. My mother was a really committed cook. She was the kind of cook who watched Julia Child and would try anything. She learned how to make great tomato sauce from her neighbor downstairs who was an immigrant from Southern Italy and always welcomed her into her house. She would make lasagna.

My mother still talks about when we spent a year in France, when I was young, because my father was on sabbatical. She would go to the markets there and buy cauliflower that, when you cut it open the water is dripping out of it, it’s so fresh. My mother had a real appreciation for fresh food. She was a good cook. We always enjoyed eating. But we did not eat chile!

Krista

Your father was a professor? Does that mean you grew up inside of institutional contexts related to universities?

Audrey

Loosely. He was a math professor and also serious bassoon player and my mother was a violist, amateur. My grandfather was a pianist and piano teacher and travelled all around, trying to make a living.

Krista

Were there symphonies? Small chamber orchestras, was there an institutional context for music? I’m thinking through the sites where we get the urge . . . for particular locations. Like I grew up in a business family that was so de-institutionalized. As a young woman, if I didn’t create a place to belong, unconsciously I worried: how could I put my feet on the ground? Otherwise, “the world” was the world of business. For me, the university is a place that is organized, that has people who are committed to a mission and they’re not organized around making money. Whatever you want to say about educational institutions, their limits, they are not organized around making money. That’s not the ideal mission.

Audrey

Right. Right.

Krista

So for me, university life was like a move to something that had a structure from some way of living that did not have a structure.

But it sounds to me like you grew up around structures of many kinds.

Audrey

Yeah. My family was not in business. We were teachers, artists. One grandfather was a surgeon. Another grandfather was a pianist. There were lawyers, professional people who were dedicated to causes. One, generations back, was a congressman. Another was an early trustee of the University of Chicago. One grandmother studied art at Cooper Union and played harp; her grandmother was also an artist and musician who settled in Wabaunsee County, Kansas. And there were writers. People dedicated to their work and associated with institutions, not part of a firm or business organization. So business is very foreign to me.

But you know, necessary, to be familiar with and [Krista laughs] you know, to manage in the world.

Krista

Are you one of these children like Marilynne Robinson, “When I was a child, I read books.” Are you that kind of child?

Audrey

I read a lot of books.

Krista

Did you have a favorite? Did you have like a little study in your room or something? Did you have a special place?

Audrey

I had my own room. I don’t have any siblings, as you know. So, if I wasn’t going to be reading, I had to find another way to entertain myself. Reading was a big part of my life. I loved a lot of classic novels. I read all the Louisa May Alcott books many, many times. I read all the-

Krista

As a child, say under 10?

Audrey

Yeah. And well through middle school.

Krista

So early childhood. Those exposures to institutions of womanhood in literature.

Audrey

I read the Little House on the Prairie series. I would start at the beginning and read them all through several times. I read the Brontes.

Through middle school, I would say.

And then, in my teens, in high school, I had a wonderful poetry teacher. And I read lots of poets: Whitman. I read Dickinson, I read Stevens, I came to love Tennessee Williams and Eugene O’Neill. I had great teachers.

Krista

Did you have a favorite book, something that made you feel a certain way?

Audrey

It’s hard to pick out one book…

Krista

That’s the thing that someone who reads a lot says. I can, I can pick out stuff.

Audrey

Oh really, what book would stick out for you?

Krista

Well, not from early reading. Mainly from more recent years, for a long time it was Cormac McCarthy. I couldn’t move beyond Cormac McCarthy. Of course, I read other things but I was having a problem with myself about this, this love affair I was having with Cormac McCarthy.

Right now, it’s been Marilynne Robinson. For a long period, I was so taken with Civil Rights literatures, and that period has passed. So as a child, I did not read. My mother might say I read. But that’s not how I would characterize my childhood. My mother was a reader, a great reader. But me . . .

Audrey

When did you discover that books were pleasurable?

Krista

Late. That wasn’t the first place I went for pleasure or for. . . knowing. And the day to day was demanding. Very. I have four younger sisters.

Audrey

There wasn’t unbroken time to . . .

Krista

No. Not because of my sisters, though they were always the background sound. But because of the way my family was in business, and we moved a lot.

Shall we talk about feminism? In this project, everyone is dedicated to Western Studies, however much we offer a complicated entry into that framework. A lot of us are working through feminist frameworks too, you’ve worked a lot through explicitly feminist points of departure – the new piece in Susan Bernardin’s book for instance. But unless we specifically ask ourselves how we embody “feminism” in relation to place, land, the question seems to slip away, elude us . . . you’d think it would be a first topic we address or know how to answer but the answer usually is slippery.

Audrey

My first answer would be that my way of thinking through feminism comes from poets and artists. From Adrienne Rich, who was such an important poet for me early on. I studied poetry, I wrote poetry. And her statements, about locational poetics and what it is to be located in a body, in a family, in a sexuality, working through that in the language of poetry. And Gloria Anzaldua’s writings, which are enacted. Her feminism is put into action through her poetry but also is theorized and a matter of reflection. That’s a model for feminist action through writing.

I also had powerful teachers, professors, advisors, and now colleagues It comes through that direction, but not through feminist theory on its own terms. So it didn’t come out of-

Krista

Gender Trouble [Judith Butler] for example.

Audrey

Right, that’s not been a part of my formative experience.

Krista

In this discussion about “feminism,” do you want to comment about a direction you’d like to see Western Studies go?

Audrey

Maybe thinking about directions for the future has to do with opening up connections with other fields, with other ways of thinking about embodiment, thinking about cultural histories that are… that don’t center around conceptions of feminism as they’ve taken institutional forms.

Krista

Should we jettison the term for the way in which it gets mobilized to stand for a certain kind of history?

Audrey

Maybe. You’re probably a better person to indicate what direction it could take, you have worked through those histories and contended with them. . .

Krista

Hmm. A place to think about feminism might be the code that is invoked by the term, what are we talking about? What’s objectionable about “feminism?” Is it the association historically with whiteness? The way in which it’s taken institutional forms through either law or through political activist histories like N.O.W. (National Organization for Women) for instance? Is that what we’re talking about? The way feminism gets so associated with white women’s concerns or anti-lesbian politics (in the case of N.O.W.) that we might say the term can’t be recovered? So many queer folks feel skeptical about feminism vs queerness as a politics for them, feminism isn’t “their politics.”

Audrey

Yes, I would want to be cautious in thinking about recovery. I think it’s a question of how to include issues of gender relations and queer positionality moving forward, and to not go back to an older feminism and recuperate it. But maybe other categories are going to be more useful. I’m not sure what those categories are.

Krista

Is there a conversation you’d like to have that we haven’t touched on?

Audrey

I’m interested in how this project has shifted in the process of doing the interviews. What had you imagined and wanted it to be when you started, and how have the people you’ve brought in, and the conversations you’ve had, fulfilled that or shifted your sense of what it’s going to be?

Krista

I didn’t have a grand picture of what it would be, coming in to it. I missed people, because of COVID. I wanted to see people in person, and one of my sisters liquidated one of her retirement accounts during COVID. She said, I’m gonna spend some of this money. I was like, well, she’s got about 15 times more money than I do. But I’m gonna liquidate something too. So we bought this van. And we needed a reason to use it.

Audrey

So it’s a COVID van, a COVID vehicle.

Krista

Yeah! And my children don’t live at home anymore, so we had that new liberty. Plus in the surf project, the Institute for Women Surfers, I worked a lot personally on how to reengage a more embodied life. Surfers live very embodied lives. Being in university became a less embodied life over time for me than the life I had led before I started on this path, at age 25, to going back to college, then eventually becoming a professor. I had this whole other life that was, for a long time, my true, deep, real life. And now I’ve known José and had children and done other things and created a different new, real, deep life. But I’ve been tracking this notion of embodying my life for a while, the way it relates to the work and how it relates to the way I live. I have certain expectations for embodiment given that I lived on the beach for a long time and also how I grew up. So the questions of the project fit into those pursuits and have been on my mind, they pull at me. Perhaps the project also shows an entrepreneurialism coming out of a business family.

Last: I’ve been puzzling for at least 10 years over what’s the problem with the term “feminist?” You know this, because we’ve had a lot of conversations and done panels together at WLA. I mean, I know the problems with the term feminist, of course, I know. And yet, and yet, and yet, and yet. I’m not satisfied with answers to my questions about the problem. For very thoughtful people, more must be at stake. So what is it, what are the real anxieties about it?

I wanted to talk to people for real, and go someplace where they want to talk. Not “stage arguments” in essays, because I’ve done that, a lot. I wanted to get to know people better. Which is partly why I’m asking you about your past or family, like, what makes people tick?

And to answer questions that people have about where I sit. It’s not a one-way thing. There’s a desire to be mutually faithful here so there is context to our relations. I have been on a personal/field/political/intellectual “integration goal” for a long time.

Audrey

Yeah.

Krista

Those were starting places. But what has happened I wouldn’t say it’s been . . . happenstance. But something has come about by unconscious design. Right out of the gate, our relations with people were so heartening. We are meeting outside of departments, outside of the conference context where people are presenting material. The project opened up something different. And I found that it has produced wellbeing, for me, and for the other people.

Jose’s thought is that something of a more de-institutionalized kind of research project has emerged, which is helpful right now since so many people’s budgets are strained and . . .

Audrey

That’s really true and actually you reminded me of a conversation that we had . . . it was one WLA where we were walking with Melody [Graulich] and Nancy [Cook], . . .fantasizing about having a weekend together, . . . maybe in Taos. At that time, it seemed almost within reach but also difficult to coordinate given all of our schedules. But I remember that being something something . . . ideal. One of the things I love about WLA and the people who keep coming back is that there’s this desire to recognize the value of our institutional work but also work outside of it. We are all interested in being in that in-between space. As you say, doing academic work is weirdly disembodied, because of where you have to be.

Krista

And it’s a training. it’s a profound training. Also. We need to retrain that disembodiment to engage the Indigenous “4 R’s” [respect, reciprocity, responsibility, relevance]. To think about what it means to be good neighbors. To think about what it means to undo certain kinds of settler ways of being. I mean, I’m speaking for myself, raised in business. What’s the point of your life?

It’s upward mobility. It is being efficient. Relationships are . . . not to say that relationships aren’t important in my family, that’s not fair. But I’d say it’s a very white kind of sociality with a particular class inflection, especially early in my life. That’s too vague, but I don’t want to digress even more.

All of the institutions we’re in are really struggling to define why humanities should be funded. We are also trying to convert what we know to share with people who are not going to have conversations in a way we would as scholars. And not sacrifice the sophistication of concepts as a way to engage the public, but to rethink how we talk about what we do. Can we say things about ourselves, for instance.

Look at writers. I’m with a lot of writers at Rice, and elsewhere. They talk a lot about themselves in relation to their work, and their work in relation to their lives. They’re trained to talk about themselves, and they know how to do it. It’s not shooting from the hip, it’s curated.

Audrey

Sure, absolutely.

Krista

I would like scholars to be able to do that better. One of the things that I could imagine for our project is having a follow up symposium where we could talk about “what it would mean to me” to write across genres that make everybody really nervous. If we don’t know what we’re doing, this should make us nervous because we shouldn’t be saying a bunch of stuff we’re not prepared to stand up and speak. I’ve done that at WLA where I wasn’t prepared for the feelings that came up. I don’t think that kind of revelation does anyone any good, although writers do have that experience happen to them. They also handle it well, actually.

Audrey

I’ve just come to Sante Fe from San Marcos, Texas, where I was part of a group of contributors to a scholarly volume [about the writing of Sandra Cisneros]. In San Marcos we were all talking about the difference that Cisneros always had in mind about the distinction between the author, the public persona, versus the self that comes through in the writing. As scholars, I think we move between those kinds of identifications.

The questions of our personal investments become entwined with the work we do, with the institutional work we do, and also with what we publish, and what we choose to put out there. So the question of the personal, I think, becomes a little more complicated. A lot of it goes into the work and gets translated into forms that are scholarly. . . And in some cases, the forms have to do with institutional work. . . .I’ve learned a lot from Susan Stanford Friedman, who talks about how academic situations matter. What difference are you making in access to knowledge, or providing a structure that is equitable for women, and scholars of color and students who are first generation students? That work matters, and it gives a space for transformation of knowledge and transformation of fields that’s beyond the reach of an individual writer or an individual scholar.

Krista

I’m thinking now about Stephanie LeManager and her phrase “the unapparent archives” that are at the margins of our work often, and of why we will or won’t or can’t say certain things, and how they motivate us anyway [from Living Oil]. They seem to me to be very fruitful places to try to push on in a loving way.

What she’s talking about is growing up with oil and growing up with a family who owned oil and owned very specific small oil derrick patches in West Texas. She would go to the patch with her father as a child, it was a dreamscape for him. That’s why I’m asking you these kinds of questions too. They help us to think about what we’re up to.

I’m teaching a lot of students ho to write, how to make pitches, not arguments. The pitch is something we as scholars don’t learn. I’m trying to figure it out myself. A pitch versus an argument.

Audrey

It’s not promotion. . .it’s like an enticement. Inviting someone to listen and be interested and want to hear more.

Krista

Yes! And it’s appropriate to a general public audience. That’s how you pitch nonfiction to a trade book editor. I’ve been taking that seriously and training my students to not craft arguments which their parents will never understand.

Audrey

Right. They ask, who you are arguing with? What are you arguing against? And then you say, Well, it’s very complicated, it’s a scholarly thing. But then no one really cares outside of academia.

Krista

Taking seriously the crisis of the humanities, the need to not cordon off the knowledges we have for some small group of people.

And to train students in ways that take seriously that we have things to offer. Can we cross the town/gown divide? What skills does it take to do so? It seems to me it takes skills that are related to not restraining ourselves in such a disciplined ways. I mean, I think about myself, I was not a restrained person when I came into academia, and I’m so restrained now.

Audrey

What happened? [laughs]

Krista

It’s so incremental. . . Then when or if we undo it, it’s a mess.

So maybe you’ll let me ask at the end, do you have an early memory of something “feminist?” It’s very interesting to see where people go with this question and how we can start to protect it or ourselves, because it isn’t what we think of as “feminist” now.

Audrey

An early memory. I think of my family of strong women and unconventional women and women who have chosen not to conform in lots of ways. That was definitely true of my mother, who cared about music and who wore Levi’s and a chamois shirt every day of her life. She ran marathons. More than anything she loved her time in New Hampshire on Lake Winnipesaukee and the freedom of skinny dipping in the lake and playing music and doing what she wanted to do.

That was a deep part of my childhood.

My thinking/feeling about my mother and her independence changed when I was a teenager. She suffered a serious injury from a bike accident that required brain surgery. It took a few years for her to recover as fully as she could, but she was not the same person afterwards. Would she have become conscious of her feminism and acted on it if she hadn’t been injured? How would she have exercised her independence as an older woman? Hard to know.

The question of her feminism, and that of my grandmothers, aunts, cousins, and other female ancestors, is complicated. I see patterns of independent placemaking, in the West and elsewhere, as well as the need to adapt to the demands of husbands and children and to move accordingly. For some, the combination of economic privilege and choice of how to live afforded great freedom — true of some women of my mother’s generation and younger who became language teachers, or went back to the land in Maine and built a yurt and then left their male partner for a female partner, or lived alone and traveled the world, or created new homes for themselves in Puerto Rico or Fiji. For others, there never seemed to be enough money for either stability or such freedoms; their mobilities were not of their choosing.

My grandmother had a very independent life and her mother actually grew up in Denver, and then came back to Boston.

I have other relatives who came from the West and moved around and came back and moved around a lot.

Krista

That’s a less known kind of migration pattern.

Audrey

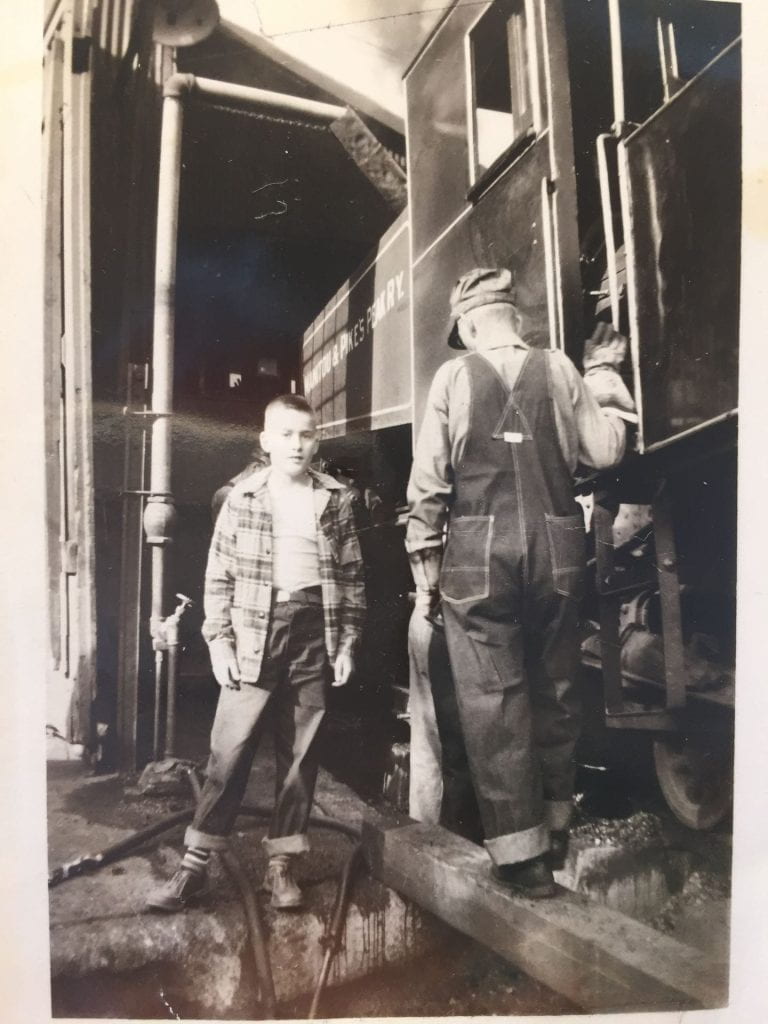

Yeah, [it’s a pattern that goes back] many generations. On every side of my family, we moved. We were in Nebraska, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma — and Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Florida. My father was born in California and made his way back to the East Coast, as did both grandfathers. Here is a photo of my father as a boy in Colorado, fascinated with trains, as he has been throughout his life.

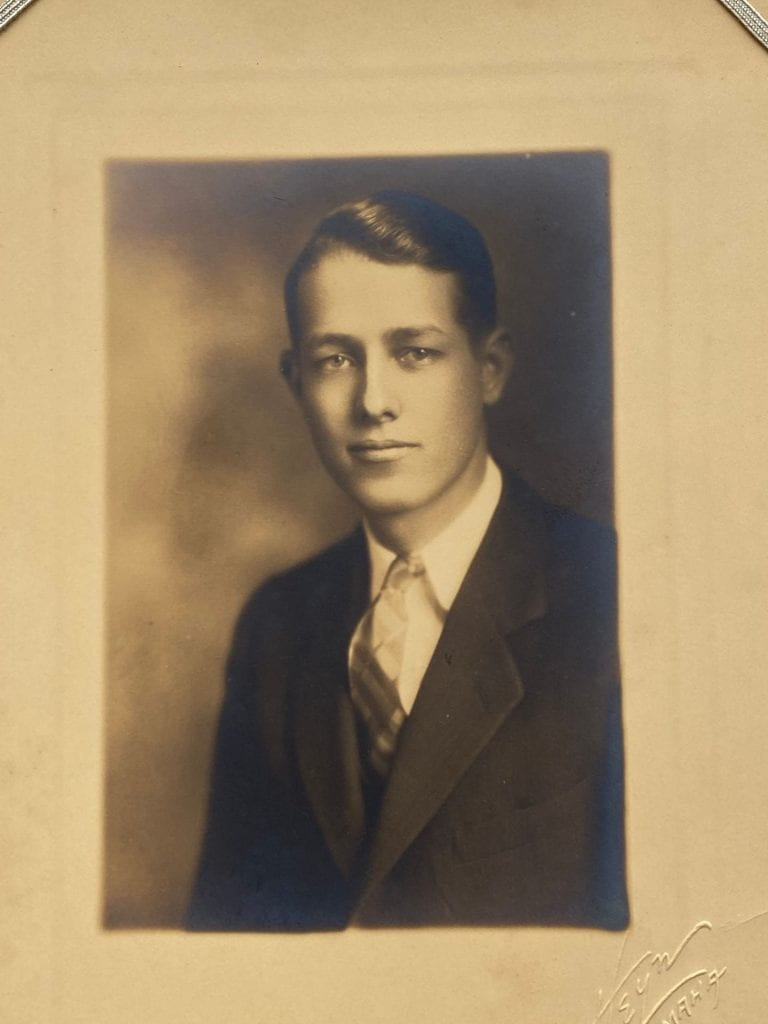

One grandfather grew up in Peru, Nebraska and had his portrait taken by the Heyn studio in Omaha, known for its Sioux portraits, before leaving for medical school in Philadelphia and practicing surgery in Boston. My other grandfather, the pianist, grew up on a farm in western Kansas and came to New York to study at Juilliard.

Portrait of Audrey’s grandfather, Richard Overholt, taken in the Heyn Studio, Omaha, Nebraska c.1920.

An early memory of feminism is the women who were both creating the conditions for their lives and ready to move. Because of their marriages and their families, they had to be ready to create new attachments. That’s deep in my lived experience of my family, and something that I felt I had the power to learn from . . . and shape for myself.

Postscript

Audrey wrote to me later to say more about her family history. She was reflecting on the many travels across generations into and out of Western spaces, the stories her parents overheard and that she overheard from them. Reflections, she reported, that rekindled an interest in mapping her family histories. When we edited this blog she added a few more details and photos.]

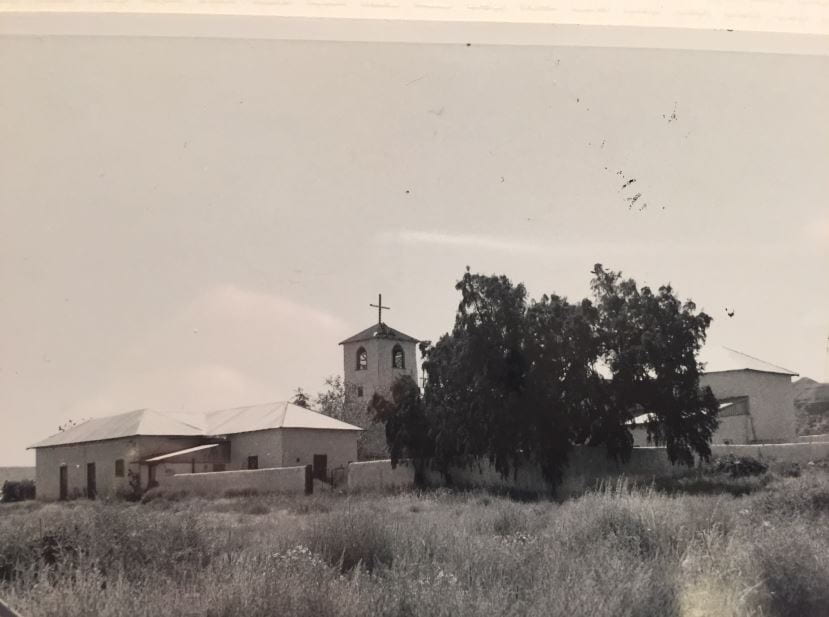

One story she shared came from her father, who remembered a great-uncle who had a place in Hatch, New Mexico, the location of New Mexico’s annual Chile Festival. The story comes with a photo of a church provided by Audrey’s father and in it the outlines of the musicians and artists and medical people who make up her people stand out.

William Mitchell, Audrey’s great-uncle, loved his converted church in Hatch, NM. Photo taken in

the 1950s.

Here is Audrey and her father talking about his great-uncle.

“This great-uncle Mitch lived in Boulder and Denver from the late 1940’s on. His main business activity was selling the Schulmerich carillon systems to churches and municipalities in the whole Rocky Mountain area (Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, Montana).

The system had been invented in the 1950’s and used actual small metal bells whose sound (when struck by a player-piano like mechanism) was amplified and propagated via loudspeakers on church towers. Quite a Rube Goldberg device [meaning overly complicated], but the sound produced was an impressive approximation to a real carillon with enormous bells.

My father’s mother (Marguerite Mitchell) and Mitch were very close, and my father heard a lot about him through her. Uncle Mitch was evidently a good salesman, and dealt with Mormons and all the other disparate cultures of the western states. This involved long car trips, and Mitch loved his big cars. His second wife Jerry was a radiologist and photographer. They acquired the abandoned church property in Hatch N.M. sometime in the 1950s, and loved to go there.

What Audrey says is that she and Lisa Tatonetti searched the photo together on google, since in fact Lisa recognized the place from a previous visit to Hatch!

Today the place appears to be an Airbnb. Now that’s a very Western kind of tale.