The Missoula Public Library is Randi’s choice of place for our conversation. It is a state-of-the-art facility any city would envy, created by local architects A&E Design in partnership with Minneapolis-based Traci Lesneski of MSR Design, library-museum specialists. The new library is billed as cultural house, makerspace, and center for lifelong learning. As Randi has recently written in “Sustaining the Humanities Across Rural Montana,” cultural institutions like museums and libraries have been essential workers, so to speak, in Randi’s own educational experience. Raised in rural eastern Montana, educated at Rocky Mountain College in Billings before pursuing a PhD at University of Arizona, Randi knows firsthand the importance of cultural infrastructure in “keeping ideas, stories, and conversations alive and well.” As a homegrown culture advocate, she’s a perfect fit for her appointment as Executive Director of Humanities Montana. To read more about Randi’s work, see here.

Randi waits for José and me in the library foyer, bearing a box of cookies from Bernie’s Bakery in Missoula. “The heart,” she tells us jokingly, “is Missoula.” It’s such a thoughtful Randi-like thing to do. She brings treats to parties, though that term isn’t quite right for our “theory parties” in hotel rooms during academic conferences, gatherings of colleagues and friends who discuss feminist conceptualizations of place/region. Not enough wine at those events to call them parties. But Randi has been a mainstay of the gatherings, always up for tricky conversations.

This extraordinary library space and level of investment in public learning centers is very hopeful at a moment when libraries are being closed or converted to other uses (including ones at my own sons’ public high school). Humanities Montana houses some of its programs in the library and when Randi shows us “The Democracy Project” banner, I get choked up. It’s so refreshing to see youth initiatives that encourage young people to research issues they really care about.

I understand, the better I know Randi, that facilitating tricky conversations is her signature skill. As a professor at Austin College, in Sherman, Texas, Randi taught toward and has written about Sherman as a town housing the first Confederate statue erected in Texas. Indeed, she shows how classic nineteenth-century literature (Hawthorne, Poe, and Stowe) can be taught as a type of Confederate monument to ideologies of white supremacy. When I ask Randi for an early sample of her feminist work, she sends along the Epilogue to her 2008 dissertation. It reflects on the frustrated leadership attempts of her evangelical grandmother as well as herself, both of them faithful women whose talents warrant pastor or elder aspirations except that women are disallowed. This reflection is tempered fundamentally, however, by the particular white nativist vision of the afterlife. The white supremacy of evangelism is a cautionary tale Randi brings to her vision of feminism.

The Where of Here: Missoula Public Library

Krista Comer. You’ve been showing us around, Randi, telling us about the combination of state funds, private funds, that built this quite amazing place.

Randi Tanglen. I wanted us to meet in the new Missoula Public Library, because it’s so connected to the type of work I’m doing with Humanities Montana, which is a State Council of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Our mission is to infuse the public humanities into the daily lives of Montanans. Libraries, public libraries, are so central to that work. As you saw, we have one of our current initiatives at Humanities Montana, the Democracy Project, housed here at the Missoula Public Library and two other libraries in Montana, where young people research an issue or something that they really care about. And they use the information literacy skills that the library provides to research a local issue, and create a solution for it that they can work on together and to make them feel connected to their community and empowered to take action in their community.

Krista Comer. Do adults comment or do research for the Democracy Project?

Randi Tanglen. The Democracy Project is for high school students. But we have other programs for adults around issues of civic engagement. We just wrapped up four virtual panels, from an initiative called Why it Matters. This is programming on civic and electoral engagement about different kinds of political power that Montanans have. The virtual panels we did, during the pandemic, covered topics like, “The Purpose of Protests,” “Rural/Urban Political Divides in Montana,” “The Native Vote in Montana,” and “The Political Power of Young People.” Those are conversations we’re having right now.

For the Rural/Urban Divide panel, we had almost 300 people registered and attending. That was new for us, to be able to reach such a large audience. Especially in a geographically vast state like Montana with lots of remote rural communities, learning how to do the virtual programming on Zoom made our programming so much more accessible. Before the pandemic, we were known for the one-on-one conversations that our humanities experts would facilitate in libraries, museums, community centers, churches, those types of places in Montana communities. But now we’ve been able to make our programming more accessible during the pandemic. Going forward, it’ll be about finding a balance.

Krista Comer. I have heard from people working across academic humanities and the public humanities that they observe that the public humanities can be more alive than humanities in universities. It has the possibility of growing in ways that academic humanities are struggling to do right now. The defunding of the humanities in university budgets, the delegitimizing of humanities knowledge as the importance of the STEM fields grows, and professionalist training grows in universities. What are you seeing in Montana right now about the possibilities of public humanities versus the academic humanities?

Randi Tanglen. I have been thinking about that a lot, especially over the past year. This isn’t a fully articulated thought or theory but our mission is that we serve communities through stories and conversation, which could be taken as a watered-down version of what we do in the academic humanities because it’s not focused on discipline and rigor or writing or research. . . . But when I talk to people and look at our programs and the impact that they’re having, I find that what people outside the academy are really looking for is the multiple perspectives that the humanities provide and the different voices that the humanities are able to bring together and the nuance and differences those perspectives bring out. Whereas many times, in the humanities disciplines in universities, our writing and research is organized around “the intervention,” or finding an argumentative niche and throwing everyone else who disagrees with you or came before you under the bus. For the public humanities, the work is more about the conversations and bringing the voices together.

I do think a feminist method does more of that, of bringing voices together, experiences and stories together, like the work that you’re doing. I really liked what you wrote in your About Us statement, of needing to find ways to listen to and learn from each other. I thought of that as an orientation towards public humanities that we’re trying to do, too at Humanities Montana, especially at this divided political moment, and in a changing Montana that is becoming more red and more conservative and falling along the divides we see in national politics.

Krista Comer. There’s at least a couple of things to think about there. One has to do with the feminist parts of public humanities, or the specific rural/urban divide or red state/blue state divide we were talking about a minute ago, before we started the camera, about “the white problem” in Montana. We heard from Clark Whitehorn (Executive Editor at University of Nebraska Press) and Charlene Porsild (CEO, Montana History Foundation) about “Montucky,” and the cliques in high schools that are called Hicks. The Hicks are in a way, white nationalists, gun rights defenders. At least in Helena, we heard, the cliques were the goths, the jocks, and the Hicks and the nerds. That category of “hicks” must in its own way live in a lot of different places. But I was thinking about feminist methods, and feminism as a theory that engages difference and conflicts between women, feminism is built out of that history. So the question is what can a feminist public humanities do about Montana’s white problem? You know, I’ll just throw that out there. [laughs]

Randi Tanglen. Oh wow, thanks!

Krista Comer. We can put it out there, we’ll chew on it the whole time that we’re talking.

Randi Tanglen. My mind’s going in a few different directions. But I can speak to my own experience a little bit, of that “early feminism” you and I emailed about.

Krista Comer. So to remind us: you sent me the Epilogue to your dissertation, “Feminist and Religious Legacies.” And it has to do with your grandmother, Rickey Tanglen, and her histories of evangelism in eastern rural Montana, with the Lutheran Church and the Lutheran home missions she founded. You talk about how your own feminism grew from what you learned about her, which was that she could not become an elder or preach, and her frustrations and anger. And then what you experienced yourself.

Randi Tanglen. I’ll talk about that, yeah, and it will bring us back to the issue of whiteness and feminism.

I grew up in rural eastern, northeastern Montana. Close to the North Dakota border. I was born in a town called Sidney. You’ve heard of the Bakken oil fields? It’s out there. My family moved away when I was 10 because of that classic boom and bust economy of the West. There was an oil bust, and my family ended up moving to different parts of Montana. But that’s where my dad’s family was from, and where my parents moved after they were married, and started their family. My dad worked in the construction business, not the oilfields. And then later on, he became a journalist at one of the local newspapers. My mom was a stay-at-home mom, but with the economic realities of the oil bust she eventually went to work full time, and had a long career in the federal government.

One thing that was really important to me as a young person was being part of a church, that Lutheran Church that I wrote about in the Epilogue. It was a place where I experienced so much love and acceptance as a child. But then, as a young person, I started to see some of the inconsistencies and especially the double standard around gender. I started to ask a lot of questions and eventually realized I couldn’t ask questions without becoming a black sheep. I felt rejected by the church, this place that had been so loving and accepting of me in this small community that I was raised in. I later found feminism, which also provided a place of belonging, and, what religion had provided before, something bigger than myself, something to believe in, something that was right to my mind as a young person, a college student. I went to a really small college in Billings called Rocky Mountain College.

Krista Comer. Can you remember a time you asked the wrong kind of question? However, it came out, whatever you noticed, even in its vaguest details?

Randi Tanglen. In my family, and my community, there was a lot of tolerance. It was more like, “Oh, that’s Randi.” Or, “that’s just Randi being a feminist.” It was during the Rush Limbaugh era. It was like “Oh, you’re being a femi-nazi,” or teasing me, not taking me seriously, when I asked “Why can’t women be leaders in the church?”

Krista Comer. Did you want to be a leader?

Randi Tanglen. I did.

Krista Comer. What did you want to do?

Randi Tanglen. When I was a young person, I would have seen myself as a pastor. I was really interested in theology and . . .

Krista Comer. Did you feel you had a calling? It might be hard to claim now, with everything you know today, but to think back to the young person?

Randi Tanglen. I don’t know… I think when I was young, I would have said that. But there wasn’t a clear path for what that would look like. I think also that’s why academia became an option and teaching spoke to that…

Krista Comer. I keep interrupting, but like you’re 12, 13, 14?

Randi Tanglen. No, this is more teenage and early college years.

Krista Comer. You were going seriously to church up until you went to college?

Randi Tanglen. Yes. And even after.

Krista Comer. So this is a long term faith path, and commitment.

Randi Tanglen. Yes, and wanting to bring the worlds together, feminism and religion. In my dissertation, I was saying: Hey feminists, you need to take religion seriously, because it impacts what people do in the world. And in academia, and especially with feminism, there’s a secularism, we don’t know what to do with religion. Even now, we are blindsided because we haven’t understood that religion shapes how people vote. It shapes how people live their lives and the actions they take in the world. That’s something to take more seriously, so we can engage, and be more effective as feminist teachers and as feminist intellectuals…

The other part that wasn’t in my dissertation was that my mom was raised in a Mennonite farming community in northeastern Montana, even more remote than Sidney, in a small town called Lustre, which is – and this is where the whiteness piece comes in – is on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. To this day, it’s still not clear to me how Mennonite homesteaders in the early 1900s were able to get homesteads on the reservation. There’s that long history and dynamic too that as a young person, and even now as a middle-aged person coming back to Montana, and really having to grapple with my Montana heritage, what that means and meant?

Krista Comer. Do you and your mom have conversations about the Mennonite history? Or its gender order?

Randi Tanglen. Yeah, we do. And she and her cousins and her sister talk about that a lot. The gender order, but also what it meant to be a white ethnic community on the reservation. And those legacies…. What do we do with that, now?

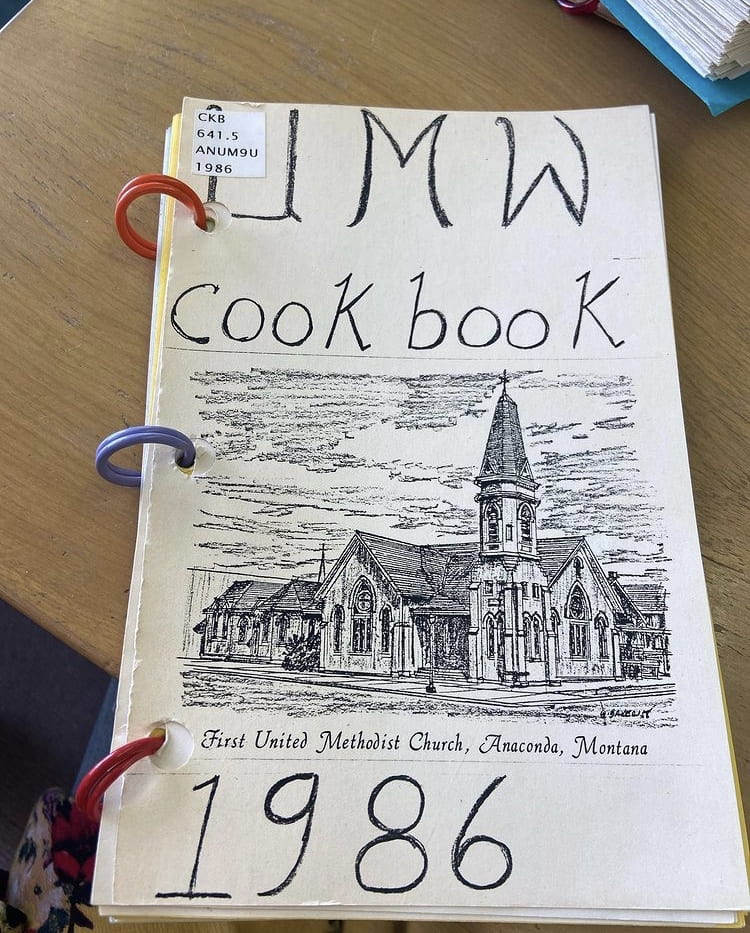

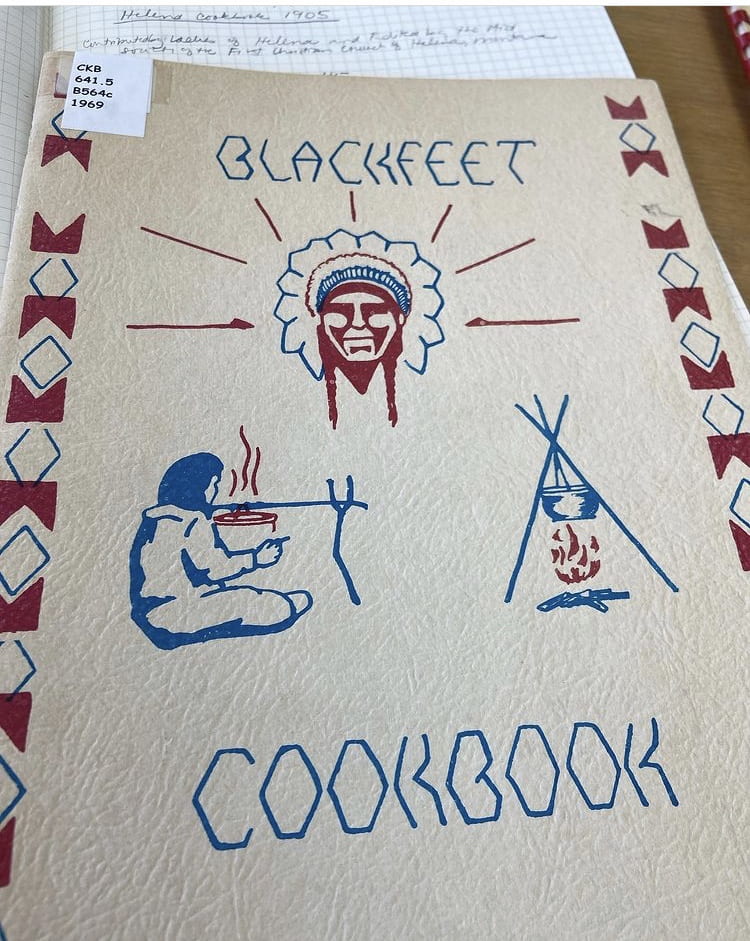

And that gets to the cookbooks…

Krista Comer. You are referring to the recipes that you posted on your Instagram account?

Randi Tanglen. When I had just finished my Master’s degree here at the University of Montana, actually, with… I don’t know if you ever met Jill Bergman? Jill passed away a little over a year ago before I moved back to Montana. But she was my mentor and a great feminist mentor. And when I was finishing my master’s thesis with her, I started thinking about the church cookbooks that my mom had in her cupboard that were from Lustre, from the Mennonite Church. And they recorded a lot of the food traditions from these Mennonites who came to Montana from the Ukraine, where they’d been living. I thought that was fascinating. Jill had me thinking about historical recuperation and historical recovery work. I was thinking, where is the Montana women’s literary tradition? Looking for women’s voices and women’s stories in unexpected places. I actually received a research grant from the Montana Committee for the Humanities, which is now Humanities Montana!

I researched and did interviews with the women who made these cookbooks in eastern Montana. And my question was, did these cookbooks provide community for women who were in these remote Montana communities that are associated so much with isolation and loneliness? What I found was that they actually provided unexpected leadership opportunities for women in very conservative communities that had limitations on women’s role in church and community organizations.

Those pictures on my Instagram were from community cookbooks at the Montana Historical Society Library in Helena. Looking for the earliest cookbooks, I think it was 1883, the earliest one from the Butte area. So again, those strands of women not receiving the recognition they deserved, and me wanting to help those voices come out. And then . . . all the strands of feminist approaches to that, and religion and family and places all tied into one another.

Krista Comer. Did your mom cook Mennonite for you when you were growing up? What would be a Mennonite meal?

Randi Tanglen. Yeah, yeah, that’s why I was interested in it. These were things that her aunts and grandmas would make for family events. You want an example of a Mennonite meal?

Um, Verenika, it’s like a dumpling, so it’s like pierogi, but it has cottage cheese, and a heavy cream gravy that goes with it. It’s very time and labor intensive… You have to fold over these little pastries and pinch them together. My mom always observed: how did pioneer women find the time to do that? The fact they did says that they were valuing something, or trying to maintain some sense of a culture or civilization in their homesteading life.

Krista Comer. We began the conversation about the where of here. The where of here is in the library we are right now, but it’s eastern Montana, and histories of women evangelists in eastern Montana, and the issue of women’s leadership.

Randi Tanglen. In Montana they say there are six different Montanas. Living in Missoula in western Montana is so different than eastern Montana, which is plains and the prairies and the hills.

One part of the mission of Humanities Montana is that we push ourselves to reach the Sidneys and the tribal communities in eastern Montana too… Are our resources going to those places? That’s hard to do based in Missoula. So that’s something we think about a lot.

Krista Comer. A sense of place, for you, is Sidney? Plains and prairie?

Randi Tanglen. Yeah, it is prairie and dry. And churchy and domestic space, female space was how I felt them.

I think a point of your research, Krista, is that the West is many Wests, the West is a contested space, and a contested critical term.

For me, the West is rural, and coming from rural communities, that’s where my sense of justice comes in. They are overlooked, underserved communities. And that is one thing that I really like about my work now is that we’re able to bring resources to those communities, especially through the American Rescue Plan and the CARES Act. To me, West is those eastern Montana spaces.