We meet at a café on a rainy day in Corvallis, then find a dry place in Susan’s office to set up. Since 2017, Susan has been Director of the School of Language, Culture, and Society, at Oregon State University. Today the campus is closed in observance of Juneteenth. Otherwise, Susan had plans to have our conversation in Peavy Hall, the newly redesigned College of Forestry facility whose views of local landmark, Mary’s Peak (highest peak in the Oregon coastal range), coupled with an installation by the Wakanim Artist Collaborative, “Things Remembered in the Flood,” make it a resonant meeting space. Wakanim translates as “many canoes.”

The location called out because in Spring of 2022, the College of Forestry made a major hire and Susan served on the search that helped bring in Dr. Cristina Eisenberg in the inaugural role of Associate Dean for Inclusive Excellence and Tribal Initiatives.

Susan and I have known one another now nearly thirty years. We met at WLA, but our memories differ about when and where. Family, children, health, love of Santa Cruz, job issues, and discussion of our respective fields in feminist and Indigenous Studies, these have been our source materials for annual commiseration. In 2018, we co-edited a special issue of Western American Literature to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Western Literature Association (WLA) and think forward about hopes for the future.

Susan’s new major undertaking Gender and the American West of the Routledge Companion Series, is about to appear at 35 essays strong. No editor that is not Susan Bernardin could have brought together such disparate fields and people and then held space for coexistences as vulnerable as ours. She is a right person to talk with about doing our work in the heart of legacies of conflict and mistrust and the need for one another nonetheless. See here for the Introduction that holds the pieces together, and here for Susan’s full bio.

I have come ready to listen, but also to listen for openings that don’t lead us in directions we both know too well. Susan is practiced at thinking and living some of the Living West project’s most vexed issues – issues of settler whiteness and the ways whiteness can take over a room even as one tries to displace it. Issues related to feminism and the ways so many women of color and Indigenous women remain aloof to the term and its presumed politics. And then there is “West” . . .

I’ve been anticipating this moment well before today – I wanted to begin in Baltimore, the previous Fall, when Susan and I attended a SSAWW (Society for the Study of American Women Writers) conference. We sat on the same panel, “Feminist Regionalisms Now,” and after it found ourselves in an organizational context unlike WLA because, at SSAWW, we had less dense networks of friendship and a lot more time for dinner, walks, catching up. We agreed to wait on the Living West official conversation because it was just too much. The conference venue was stripped down, closed restaurants. Still at one point I broached a question that had that “interview vibe,” asking Susan about early memories of being a feminist. She pulled back, tilted me an askance face, and teased, “Are you interviewing me?” Of course, then I had to stop.

It was better to rest and reconnect anyway, to notice Baltimore was a first conference post-COVID, to take photos of the Dragon Boats in the Baltimore Marina and imagine our time as a feminist rest stop.

Finally in Corvallis we talk, at last!, about those early times that put Susan on a feminist path.

She recalls an upset between her mother and a friend when they learn some do but some don’t support the ERA. She recalls, at ten or eleven, walking the long way to school to avoid the house of a boy who harassed her. She was not going to give him another chance. A different time, on that same street, Susan and a friend were run off the road into a field and then followed by two white men in a pick-up truck. Susan remembers them looking directly at her, accelerating, and laughing. She was terrified, for them it was sport. Then there was the indignant memory of the end of a children’s book she got out of the library in the third grade. The boys “gender up” and tell the girls to bake cookies while they solve the mystery. What a memory of anger that literary scene left behind.

We talk about the Marlboro man and Virginia Slims — you’ve come a long way baby! How can it be that cigarette ads were signposts of young white feminists coming into consciousness? About the difficulty of making space for reflection, and the efficiency culture baked into our lives that rules over us.

Susan tells us about her maternal great grandmother traveling from Ireland in the late 1800s to Massachusetts, the sisters working as domestics, as her children were steered toward education. One of the sisters became a nun in San Francisco. Susan’s maternal grandmother ends up leading the Massachusetts State Federation of Women’s Clubs. The sisters had high school degrees, some had professional/technical training and worked as teachers and secretaries. The sisters did not marry.

The refrain of “both/and” emerges as a way to express how she lives being a non-Indigenous person who works in Indigenous Studies. Thinking about the West . . . it’s impossible not to carry popular culture with you, that Marlboro man mythos and iconic history. It’s always a both/and scenario. “Trump’s administration showed the way in which the West has its pull, you know.” She is talking in broad strokes.

“I think about that line from The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, ‘No matter what you believe, the fukú [curse] believes in you.’ You know, You may not believe in the West, but the West believes in you. It’s got that gravitational pull.”

“’Ah’ . . . Junot Diaz” she says, “another author I can’t teach anymore.”

The Where of Here

Krista

Thank you thank you for making time – you go to Hawaii so soon with your family for a needed break and you still made time to see us! You and I were texting a bit before our meeting today – any chance you want to comment on it?

Susan

Right — What I was meaning when I was texting was that there’s just a lot of deep-seated stuff around the West, that doesn’t work its way out, maybe consciously.

And then the other part of it is that if you’re thinking about what does it mean to be a feminist academic, a scholarly writer of my age and generation? You’re also coming to terms with the very real day to day efforts to carve out space.

I was remembering a number of instances we have talked about before that really seeded my path as an academic. Some we laughed over, like the egregious Modern Language Association hotel bedroom interviews that were just part of the culture, and we were talking about at what point did folks in the profession say, “Are you out of your fucking mind? What is this?” Instead of like, “Okay, interviews are done in hotel rooms, and you wait in the hallway till it’s your turn, and you go and sit in someone’s bedroom and have a professional interview.”

And the way in which you kind of made that okay, in your head, as also happened when starting graduate school. . . The Whisper Network was “stay away from this professor and that professor,” and what I wanted to do as a graduate student got circumscribed.

And I look back, and I’m like, why weren’t we extending our activism that way? We were unionizing, we were marching in the streets about the invasion of Kuwait. There was political activism among the graduate students in Santa Cruz in the early 90s. But it didn’t extend in that way. And to think back and say, Well, what was I doing to not make that happen?

So for our conversation I have been wrestling with the violences in academia, however minor they may be comparatively, and also the way in which I worry I’ve participated in my own diminishment as a feminist academic working in these particular structures. But not always, right? I think of becoming a tenure-track academic at University of Minnesota-Morris, finding out I was being paid less than a male colleague hired at the same time. I went to the Dean, and they changed it. At Oneonta, my next appointment, the Provost decided all incoming faculty would not get credited time and I had already been a tenure track faculty for 5 years at Minnesota. I filed a grievance, because the Dean had made a different agreement with me when I came in to the job, and I won. But at what cost to myself to do it? And in spite of that, I did not receive the same salary increases, or get the awards that male colleagues received bestowed by all-senior-male-faculty. I could go on.

Then alongside that, not wanting to, in turn, practice harm myself on others, and the kind of inescapability of all of that together.

We don’t typically afford ourselves time to reflect in this way, Krista, right?

Krista

Yeah.

Susan

We give talks and conferences, But it’s a sense of reckoning with oneself, reckoning with choices made and not made. And reckoning with the wreck of this Western world, where the lands are burning, the trees are dying, the oceans are warming and the sea level is rising. You know, students in my Women and Natural Resources class are writing their final projects on what it means to be their age and their generation, looking to a future that is not feeling very certain. And so there’s a reckoning around that generationally as well. And that’s just heavy stuff.

And I very much am aware that the Roe v Wade decision is going to come out any day. And it’s weighing on me in a visceral, existential way. It’s another hinge moment in our country.

Krista

I really appreciate everything you’re saying.

I want to pause on your statement about an opportunity to reflect. We are in fields that would invite you to do that, right, supposedly. And yet, we don’t do it very much.

Susan

Yeah, well, the oppressiveness of this efficiency culture, where we’re constantly going, are in meetings, and supposed to be producing. I’ve virtually no time to read and write. That’s, of course, self-inflicted, because I’m in an administrative position that is extremely time consuming and demanding. And, it’s also a way I can pay it forward by taking up administrative tasks as a way for other faculty to focus more on writing and teaching. But we inhabit a culture that is hell-bent on keeping us from reflecting. It’s baked into mainstream US culture, drive through, go-go, don’t take vacation.

And that productivity model has led us to this reckoning moment that we’re in.

Krista

Right. Let’s talk about “the where of here,” have a conversation about place, where we belong and where we don’t. Where are we?

Susan

Ok. Academics are a bit of a weird lot. Our jobs routinely take us to locations that we do not have generational connections to because of the vagaries and challenges of finding positions. The question is always, how do you become related to a particular place that you may now have no connection to? This is on top of what does it mean live the complexities of life in a settler colonial nation, premised on white supremacy, in this complex place called the United States?

How do we live in relation to land that you do not carry ancestral and cultural relationships with? How to center Indigenous ways of being in relation to place, without centering whiteness or co-opting? This is very important work for white people because so often we end up re-centering ourselves.

Corvallis is a place I’ve lived in for under five years. I reflect a lot on this place. And it’s not just because I am always thinking about land acknowledgments, about how you live those land acknowledgments. These are Kalapuya homelands. Our new colleague, David Lewis, is the first tenure track Kalapuya faculty member at Oregon State. Descendants of the peoples forcibly removed from what is now called Corvallis are still here of course, and descendants are members of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians whose reservation is by the coast, and the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, whose reservation is located west of Salem. So I live those questions, I would say every day, in my life and in my work. What does that mean, to live in a place, a different iteration of “the West,” which is the Willamette Valley, and the particular histories of the Willamette Valley? And of course, of Oregon, whose histories of anti-Blackness and anti-Indigeneity flow through the state’s history, from its founding as an explictly white state, through the termination era of the 1950s. Reckoning with those histories . . . it’s always on my mind.

We are meeting in my office here in the School of Language, Culture, & Society because it is raining and cold. It is Juneteenth Celebration, all the buildings are locked. I had wanted to bring you to the Peavy Forestry Building – it’s both inside and outside, a stunning architectural work. The design offers amazing views of Mary’s Peak, the highest peak in the coastal range. It’s a site of collaboration between the Grand Ronde and local environmental groups to rename waterways and other landmarks through their original Kalapuya names. There is a great video I’ll share with you about it with David Harrelson.

So I’m still very much learning how to orient myself. There’s just so many Wests in the one. To me, it always begins with the homelands that you’re working or residing on, and reflecting not just on what that means but how you practice relationality. What does that mean? So that’s the where of here, and of the West, in terms of how I live, and work, and where I’m trying to make a bit of a difference. The practice of “positionality,” a cornerstone of feminism, means trying to be accountable to the histories that have made my being in this place possible, and how to be an accountable ally, colleague, community member.

Krista

Thank you. Thank you for that very much. One of the questions I want to hear you talk about please has to do with places that you feel you belong to, where you feel at home, or do not feel at home. I acknowledge the complexity and the layers of this kind of question for people who are so aware that our lives are conducted in lands that are previously inhabited, inhabited now, and in any case, always stolen. With all of those acknowledgments in play, I want to hear more about you growing up near the New Hampshire coast and about the rock . . . we talked earlier about the meaning of the rock to you, and the way in which the rock came back to you. Because it records a child’s moment in which there isn’t an awareness of other inhabitations, or other accountabilities. One inhabits it as though the world is as it should be.

I wondered if you would talk a minute about that rock in New Hampshire, the history of it.

Susan

Okay, yeah. So I didn’t grow up in New Hampshire. I grew up in Massachusetts, but I spent summers in New Hampshire and I still go to this beach, Rye Beach.

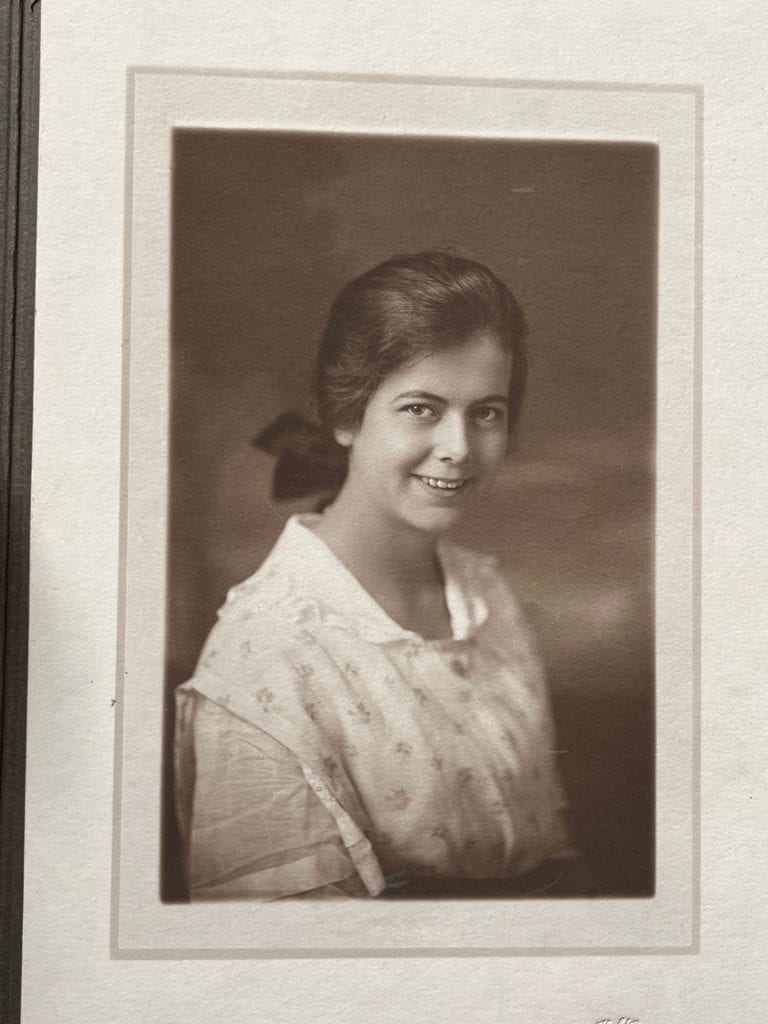

New Hampshire has only 18 miles of Atlantic coastline, not what you typically think of as “coast” in New England like Maine or the Cape. I think that my story of the rock is really . . . it’s about continuity and change, (the paradox of continuity through change, and change through continuity. As someone who descends from immigrants, from Ireland and French Canadians, who have a more complex ancestry, I would say that the only place that I have experienced intergenerational continuity is that beach, Rye Beach, because my mother and father both grew up going there beginning in the 1930s (for my father) and the 1940s (for my mother), without knowing each other.There’d be big family groups coming from the French Canadian side who came down from Quebec in the end of the 19th century and settled in those French Canadian communities of Lawrence.

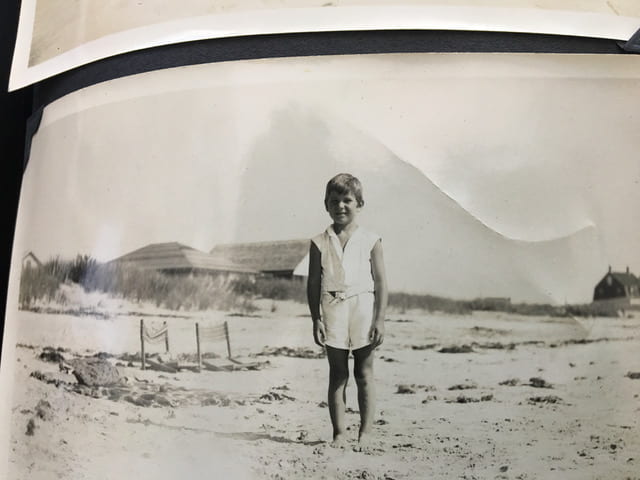

I’m struck by the continuity of the place, only in recent years before and following the death of my father, I’ve seen it in old family photographs. I’ve found all these fabulous photographs. The houses, the beach is instantly recognizable, at 80-100+ years remove. Minute in geologic time and lived history in this settler place, but for me. . . . photographs tell me that my paternal great-grandfather’s large French Canadian family came up to New Hampshire from the Lawrence area for beach visits. That tradition must have been carried on by my paternal grandfather, Eugene, too, because family photographs of my father and his siblings, usually with dogs, show many summers in the 1930s onward at the beach.

It’s the same beach, and it’s fascinating to me, because it looks the same, even some of the houses are still there, it’s immediately recognizable. The land, the rocks and the shape of the beach. That’s all probably a large part of it. And that large rock, it’s just striking to me the large rock is still there. Also, it’s not very large. Even though we call it “big rock.”

I remember playing there as a child, falling, scraping my knee on its barnacles, and taking my daughters down there to play in the sea water trapped around it at low tide. A great rock for sitting on, despite the barnacles.

When my older daughter was 4 and my younger daughter a year and a half, I went back to that rock on a much-dreamed visit the summer of my “chemo year.” I had spent months before that so weak and wracked by pain that I would meditate on Rye. Beach and that rock for hours on end.

So it’s an anchor (pun intended), a memory anchor for me. I’ve always loved the ocean, in all its myriad and endless iterations of shape, smell, location, and being. I think that’s just deep-seated stuff. I love the ocean, really, anywhere I go, it’s always where I want to be.

Krista

[Big breath.] Wow. Thank you. Thank you for that.

I hoped to think a minute with you also about another place I’ve heard you talk about a little — people who live on and near the Salmon and Klamath rivers– it was a discussion of places we don’t belong, where we know we don’t belong and how, how is it for us to be in those places?

Susan

Yes. Karuk Tribe homelands, and specifically the center of the Karuk world, at the confluence of the Salmon and Klamath Rivers and are . . . very special. I’ve been there many times, and it’s, it’s inspirited, you can feel it, it’s beautiful.

In the 1800s, it was hard for miners initially. It was really hard for settlers to get to the place. Phone lines weren’t even in, till the 1970s. It’s two hours drive from Yreka and two hours drive from Eureka, on the coast. It’s . . . you know, you have to know how to take care of yourself up there because it’s so far to get to stores and whatever else. Auntie Violet Super, a fluent elder whom I was fortunate enough to spend time with over a period of years, told me that once you go in the Salmon River, you always have to come back. That area attracted white hippies in the 1960s, who had a commune up there. There’s a number of organic farms and the area has attracted now a lot of cannabis operations, unfortunately, that are messing with the Klamath river.

And of course, the Klamath River has been extremely challenged by its damming – the most visible sign is the collapse of the salmon population in the River, catastrophic for Klamath River tribes well-being and livelihoods. The final steps in the restoration of the river through un-damming—the result of decades of advocacy and coalition-building, is happening. That will be transformative, it should vastly improve water quality, reduce fish disease, reopen spawning habitat, but it’s just, right now, it’s a really struggling river.

I feel a strong sense of kinship to that place. And also recognition that I’m not from that place, nor do I belong to that place.

Krista

So much we might explore. Can we talk about what those feelings are, beyond our practiced “aware” ways of thinking, how it is to be in place, as white feminists, or as white people? However you would characterize the outsiderness. Maybe you wouldn’t use those terms.

How it is for any of us to be asked, for instance, as you were as a young woman, if I remember right, to participate in ceremony. To agree to participate in ceremony because you’ve been asked. Because the help is needed. But then also to be aware of how it is to not belong.

Susan

Well, I certainly didn’t participate in any ceremony. Let me just say that. That no, there was no participation. And this was this was a long time ago. Yeah.

Krista

Preparations. Preparation?

Susan

No, attending.

Krista

Okay. Thank you.

Susan

Attending ceremonies. . . but to be a companion and help take some elders to the ceremony.

And you know, I think my position is I would never, I wouldn’t say no, if I’m asked to do that. But I certainly try to avoid situations where there’s a sense that I am asking to be present.

I wouldn’t want to overthink this. This isn’t some like, existential thing. This happened when I was much younger, and some elders were alive who I was spending time with. When I was spending a lot more time in that community. How one feels in one’s 20s and how one feels now are different. Back then, I don’t think I had the toolkit I have now to really just, you know, to sit with that feeling of betweenness. I have it much better now.

I am who I am, you know. I think, back then, it was the fear of being misunderstood as someone who was being a prying interloper, because of the history of outsiders coming in, the history of academic extractive colonialism and the very subjects I was writing about as I did the new introduction to In the Land of the Grasshopper Song, the fear that there was a way in which I might replicate those relations.

When I spent a lot of time there in the late 90s and early 2000s, sometimes I was referred to as “that grasshopper song lady,” you know, referencing the field matrons who wrote the book, and whose work I was writing about. I thought it was hilarious, because I am a schoolmarm. You know, it’s like, the schoolmarm!

The other thing is, you got to have a really good sense of humor about yourself. Don’t take things too seriously. But yeah, you announce yourself, I am “out,” you know, in my otherness and difference, in spaces like that. And given how violent that history has been, I am not wanting, in any way intentionally or inadvertently or otherwise, to make people uncomfortable.

So there is a balance and the worry, as an outsider coming in, that you are changing the molecules in the room by your very presence. So you mitigate harm, as much as you can.

Krista

Yeah . . . In the context of the field matrons, white women, they were “trying” right? Would you say, and we talked a bit this a bit before we started, that they were “as good as it gets” for white women of that era? [Laughing.] Were they something like the “best of white women?”

Susan

So the field matrons were you know, field matrons… And the question is what does it mean to be not just implicated, but to be agents of cultural genocide? And yet, in that space, trying to make shifts. That question of: if you are trying to situate them in a form of messy relationality, does it feel like you’re trying to justify or overly contextualize them being there? Really at the end of the day, they shouldn’t have been there.

I have thought about this question for decades, polishing it like a stone. They were there because of federal Indian policy and programs, they were there specifically to advance cultural genocide. The book they produced—In the Land of the Grasshopper Song–documented and affirmed that Karuk people had survived genocide across northern California in the 1800s, and were carrying on and through despite ongoing assaults, you know. Boarding schools, land and water dispossession, mining despoilation.

In related ways, Indigenous communities and tribal nations across California have used recordings and field notes to reconstruct and reawaken ceremonies, technologies like canoes, and languages. You have all these sound recordings from anthropologists in California, from which Indigenous communities have been resuscitating sleeping languages, languages considered extinct. So is the fact that that book In the Land of the Grasshopper Song, which is full of treasured family stories, right? It’s gossipy and juicy and all kinds of stuff going on. It’s valuable. But also: what’s the trade off?

Krista

Right.

Susan

Which is also that constitutive question of whether you undo systemic structures from within the institution, the university? Or are you simply kind of doing service work?

I am always inhabiting the contradictions. . . it always comes back to “what the hell are we doing with this short life?” to completely misquote Mary Oliver.

Krista

One of the questions that you ask about the field matrons, as agents of cultural genocide, and that we could ask about these various positions inside of institutions that are compromised in many ways is the larger question of: what is the possibility of relationality? Can there be hope in relations so implicated in genocidal histories? Is there anything recoverable there?

Susan

I’ve always been interested in relationships across difference – and all that that means. And I have to believe it’s possible

I do think about the question of recuperability or repairability, and I think it is a “both/and.” So think of an example of “both/and” from my workplace. Oregon State is Oregon’s land grant institution. It was purchased with funds from “expropriated” Indigenous homelands in southern Oregon. The university has adopted a land acknowledgement and that’s a step towards relationality (some would say performative relationality) but what follows from that? What about Land back? OSU is 45 minutes from the Indian boarding school, Chemawa, which is still operating!

The horror and violence of these histories, their ongoing impacts of gendered colonialism on Indigenous communities, must be reckoned with, fully, which is why I keep going back to the story of the Grasshopper Book and its afterlives. Maybe I keep reckoning with irresolvability.

But I think we, or speaking for myself, I must hold to the imperative of relationality as an ongoing set of commitments that shift. Being hyperaware of my positionality can be a tool, also it can be a trap, sliding into re-centering whiteness. . One can practice stealth feminist anti-racist advocacy in certain spaces, right? That’s really important. There’s just not a lot of Indigenous folks in the academy, right? Or BIPOC faculty more broadly.. So what’s the role of allies? Where can you make moves and shift, either via stealth or confrontationally, in different kinds of spaces? Where do you step back, and where you step in?

A cluster hire we just did, for example, is very important – I sent you the announcement, right?

Krista

Yes! It’s a great announcement, congratulations. Because you have accomplished the work of the people hired, as well as the profile of the idea behind the hire. Having done cluster hires ourselves (José and I) together . . . I respect how much work is behind the ability to articulate the language of the hire, and have the language forwarded institutionally.

Susan

I am often in all-white spaces in administrative meetings. I’m hyperaware of that. I’m not always sure other folks in the meeting are hyperaware as I am. because we don’t discuss it. It’s bumpy as hell. You will have limited capacities to make shifts.

But I’m mindful that I have a responsibility in those spaces, to advance institutional transformation.