This post is written by Zainab Abdali, the Clancy Taylor Summer Intern in Public Humanities.

The Islamabad of my childhood no longer exists. The stores I remember are gone, there are more cars and people than in the quiet city where I grew up. There were no shopping malls back then – we used to envy Karachi for its malls– but there are several in Islamabad now, including the gigantic Centaurus that towers in the Islamabad skyline. The Metrobus system, with its shiny glass bus stations and distinct red buses, is now the essential backdrop to any drive through the city. Even my friend T’s house, where I stayed this summer, was new to me; although I’ve known T for over twenty years, her family had moved here only a few years ago. This was not the house where we threw her a surprise birthday party in fifth grade, or where we watched the latest Harry Potter movie with our group of friends.

The one thing that remains familiar about Islamabad: the Margalla Hills filling up the horizon, and the piercing white of the Faisal Mosque in the distance.

Of course the city has changed! It’s been nine years since I left. The people too have changed. I remember my friends as sixteen-year-olds, when we would spend hours talking about an upcoming exam, some boyband we were crazy about, whether our parents would let us go to a restaurant together or not. This time, the conversations were about marriage, husbands, in laws, potential motherhood, graduate studies, careers. The girls I knew are now women, professionals, wives; some are even mothers.

Surprisingly, all this change in the people and places I grew up with did not make me sad. Perhaps there was no time to be sad! I was there for T’s wedding, and I was staying at the bride’s house – the epicenter of all wedding activity. Like most Pakistani weddings, T’s wedding stretched out for pretty much the entire ten days I was there, with its four formal events – the Dholki, Nikkah, Shaadi, and Walimah – and all the preparations in between each event. From distributing last-minute wedding invitations, to hurrying to the flower shop to pick up the marigolds that are a quintessential part of Dholki décor, to clapping and cheering as T’s cousins tirelessly rehearsed the several choreographed dances they were planning for the wedding day, to accompanying T to the salon and to her photoshoots – every day was full of nonstop activity. The last two events took place in Peshawar, so there was the added preparation of travel to another city, and of making sure that we packed absolutely everything that we – and especially the bride! – may need while staying at a hotel in Peshawar.

It’s strange staying at the bride’s house and being so involved in every wedding event when you’re not a family member, because weddings are such a deeply familial event in Pakistani culture. They really are about two families coming together, much more so than about two individuals. I know T’s immediate family of course, but over the course of my stay I met numerous aunts, uncles, and cousins who were arriving from various parts of the country and the world for the wedding, many of them staying at the house as well. I tried to keep the family tree straight in my head, and tried to keep track of all the nicknames that different family members went by.

T’s family, being from Peshawar, also speaks Pashto, a language I do not speak. Although they would make an effort to speak in Urdu or English when speaking to me, most of the conversations taking place in the house were in Pashto, since that is their mother tongue and the language of home and family. Sitting in the living room night after night and being the only non-family member and non-Pashto speaker, I would not understand most of the animated conversations happening right in front of me.

Somehow, though, I didn’t feel alienated. If anything, I liked that they didn’t feel the need to translate everything for me all the time. As I sat there, I felt like part of the family – like they’d forgotten there was a guest there, and simply thought of me as one of their own. Throughout my time in Pakistan, T’s family was incredibly hospitable, but I think what touched me the most was how they didn’t treat me as a guest or a friend, but as a family member. I got pulled into group family photos, joined the cousins in their late-night excursions for ice-cream or pizza, was entrusted with T’s wedding jewelry and salaami (traditional cash gifts, given to the bride by wedding guests). When it was time for the rukhsati, the ritual where the bride’s family escorts her out of the wedding hall and says goodbye to her as she leaves with her husband, my friend M and I stood to the side since the rukhsati is usually an emotional and tearful ritual reserved for the bride’s family. But T’s uncle, whom I had met only a few days ago, noticed our absence and insisted we join the family procession escorting T out, and T’s mom, even though she was crying herself, looked around for me, asked me to give the bride a goodbye hug like her family members were doing.

Rest Areas

I’ve been thinking about feminist rest areas a lot because of the Living West as Feminists project, and I had conceptualized them more as a place of belonging and familiarity. T’s family showed me a different kind of rest area this summer, one that kind of took me by surprise.

I think I had gone to Pakistan expecting to enjoy the sense of familiarity of being in my hometown, of feeling completely in place and at home. Instead, I felt out of place, but this was not an alienating or disappointing out-of-placeness – it was an enjoyable one. I enjoyed listening to the unique cadence of Pashto, and trying to learn a few phrases from T’s aunt (which I immediately forgot!). I enjoyed being able to see a different side of T, at home and surrounded by all the people who love her, conversing in the language they have in common. I enjoyed going to Peshawar, a historic city entirely unfamiliar to me, and being introduced to it by T’s family, who have deep ancestral ties to it. I enjoyed getting to re-meet my childhood friends as adults, to learn about their new lives and their plans for the future, to talk to them about feminism and sit with their differing reasons for identifying as or not identifying as feminists. I even enjoyed driving through Islamabad at 1 am, with family who were not my family but who felt like family, and looking out at a city I didn’t recognize but fell in love with again.

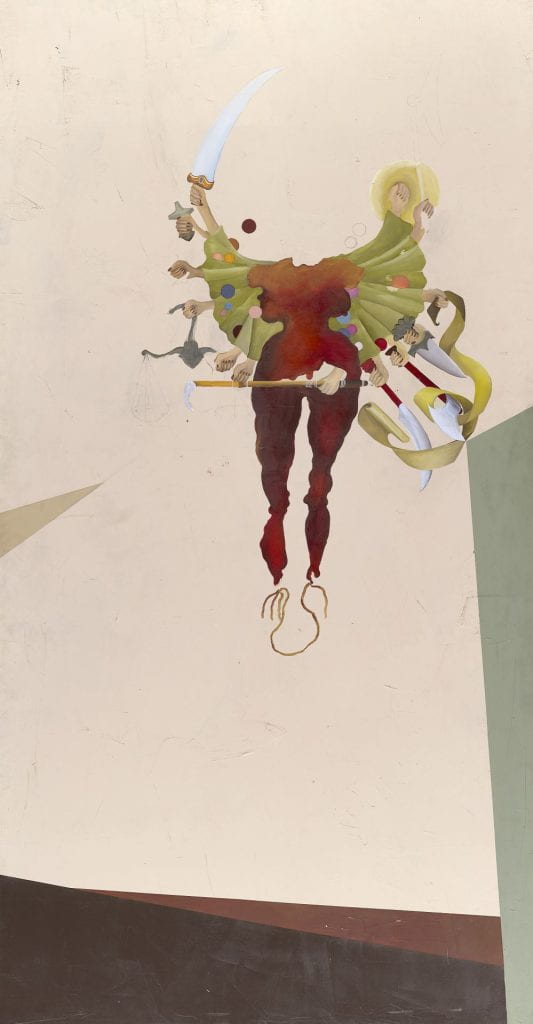

Shahzia Sikander

A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation, 1993

Gouache and gesso on board

67.5 x 37 cm

© Shahzia Sikander

There’s a renowned feminist Pakistani-American artist whose work I admire greatly, Shahzia Sikander, who has a piece entitled A Slight and Pleasing Dislocation. The work itself is one that I find powerful, but it was the title that I was immediately reminded of as I tried to gather my thoughts about this visit to Pakistan. A slight and pleasing dislocation…what an apt framework for imagining feminist rest areas, especially for those of us in diaspora. Dislocation, out of placeness, unfamiliarity – these are unavoidable sensations, but do not necessarily have to be painful ones. Perhaps we can forego complete comprehension and exact translation in the favor of simply being present together with each other. Perhaps we can think of feminism beyond precise scholarly and political arguments, but rather be able to sit with women’s complicated lived relationships to the term. And perhaps we can forego the feeling of knowing and belonging permanently to a place – a hometown – for the pleasure of dislocation, of constantly re-negotiating your relationship to place and home and the people you associate with home. In our feminist rest area, we don’t expect absolute and uncontested belonging. We know that relationality makes it possible (and pleasurable) for us to be out of place, but still be family.

Such an amazing article!

Loved reading it

It was as if I was living in the moment

You’ve penned down all our memories 🤧. Ngl I’m a fan now!

Z you are no different , a niece as T is , your presence made the event so pleasant