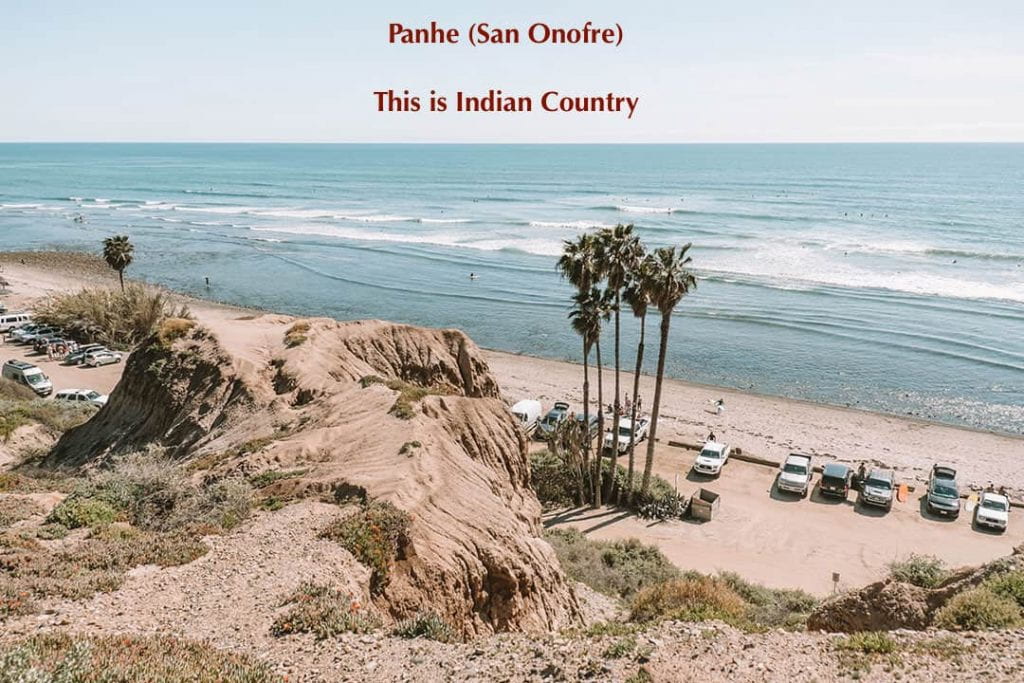

Before we wanted to become good relatives, before Dina and I knew one another at all, we were connected through Panhe –”the place by the water” in the Acjachemen language. I had written about Panhe in the Surfer Girls book. Dina wrote an entire Master’s Thesis in Native Studies showing its significance as a sacred site to the coalitions that stopped a major toll road and “Saved Trestles.” Panhe was a presence, and a teacher.

Dina and I met in 2014 through gatherings of the Institute for Women Surfers, a feminist political education project open to surfing activists. In this not-university context of surf activists but a few professors, Dina quickly became a needed leader. She offered workshops on “American Settler Colonialism 101” and tied them to how surf territoriality or localism was rooted in masculine settler colonial claims on land. The perspective was a turning point for Institute purposes and community because participants connected the seemingly unrelated dots between Native American history, surf culture, master social narratives about “discovery” and “conquest” in surf tourism, and territorialism in surfing. What people took away was a sense of the ways surf culture simultaneously benefits from, and is complicit in, an unequal structure of power that keeps Native peoples separated from their lands. This new perspective travelled with us as the Institute expanded its geographies into Australia and New Zealand where we had surf activists who wanted to host meetings and where Indigenous truth and reconciliation projects, for all their limits, are far ahead of the US in addressing histories of violence.

As the Institute Director, I urged us to put feminist forms of relationality first, to hold our relations as more important than any specific outcomes of the IWS project. Women’s relationships as feminists have a history of implosion and to prioritize relationships over politics per se was to found the Institute on more secure ground. Indigenous relationality transformed that perspective in new decolonial directions and made the stakes of our relations to place and one another far clearer, with profound implications for accountability to Indigeneous people.

Since the early days of our IWS meeting, Dina and I done scholarly events together, events for public audiences, and written a forthcoming essay about a legislated land acknowledgement in California (AB 1782) that takes about our Indigenous/settler surfeminist collaborations. We think this land acknowledgement is the first of its kind. I wanted Dina to be part of the Living West as Feminists project as a way to continue conversations about feminism. I am always half-scared when pressing these conversations, aware of histories of white feminists who can’t see their blindspots. But being good relatives requires courage and risk, being accountable is an active process.

When we get to San Clemente, Dina has José and me over for dinner with her husband Tom. We hang out in San Clemente a few days. Dina and I go to lunch. Of course we have time at Panhe. I feel a coming of full circle personally in our relations – as someone from the US West, California, a counterculturalist, a feminist intellectual, a writer. I feel blessed for our time.

For Dina’s full bio, see here.

The Where of Here

Krista

We’re at the San Mateo Creek Campground, that’s one name for where we are. Panhe is the Acjachemen name. Historically this was among of the largest Acjachemen villages, it’s 8000 years old, and remains a ceremonial, cultural, and sacred burial site.

We are really happy you brought us to this place.

Dina

This is an important place for Acjachemen people, and for me personally it began here — certain strands of my work around environmental justice that eventually became the book As Long as Grass Grows, and the surf work. It’s the site that shapes my thinking as it evolves, how I’m writing about it, and how I hope to convey a message to other people about accountability, what accountability means, and my own personal accountability, because that’s the story. And it is a story.

It began in 2010. I had just reconnected with Tom [Whitaker] and we were moving forward with our relationship. I had come here to San Clemente to visit. There was an event that happens every year called Earth Day at Panhe. It started after the toll road battle. Because of the “Save Trestles” campaign, a coalition of a bunch of diverse groups fought the building of this toll road which would have come literally right here, we would be in the path of that highway. Just imagine a six-lane highway coming directly down this watershed and creek bed through the campground right next to the burial ground! That’s what people were up in arms against. It was going to disrupt the creek bed so badly that it would have likely ruined the wave quality at Trestles [a world class surf break at the mouth of the creek]. Trestles was the surfers’ concern, the ecosystem the environmentalists’ concern, which was spearheaded by the Sierra Club. Native people came in toward the end.

There is a whole story about how these interests converged. But first it was the environmentalists, then the surfers. When Native people came in, it was not even the tribal council. It was a Native grassroots group led by two women. Angela Mooney D’Arcy and Rebecca Robles, called the United Coalition to Protect Panhe. Panhe is “the place by the water,” that’s how the Acjachemen people know this place. So they got funding to do a one-day event, a festival, to celebrate the saving of this place, from the toll road. It’s a lovely event, the community comes out, hundreds of people come just right down there where there’s a big open area, and they have vendor booths, dancing, and exhibits. Tom and I came to that event, I didn’t know anything about the Save Trestles story. When I learned about it it was so interesting to me. I needed a topic for a Master’s thesis, and I knew immediately this was it. That history is what I’m going to study. How did it happen that this Native sacred site was able to get saved even though it’s not a reservation and the tribe is not federally recognized? There are all these strikes against them.

Krista

Part of the story has to do with the California Coastal Commission?

Dina

It’s all about the Coastal Commission. Because they had jurisdiction to deny the final construction permit. What I looked at was how much did the fact of this being a sacred site factor into their decision?

And it was pretty major. But the coalition activists didn’t acknowledge that. To this day. That was what was so frustrating. Surfrider Foundation didn’t acknowledge it, environmental groups didn’t acknowledge it. But Native people did. There was the testimony from one particular Commissioner who nailed it, Mary Schallenberger, she really understood that, for Native people, the concept of sacred is different. You can’t move a sacred site like you can move a church – that was one of her statements.

Krista

When you think of Panhe as a place of accountability for you . . . would you talk about ways you are thinking about accountability? Perhaps as a Colville person, or as a surfer?

Dina

It began with my relationship with Rebecca, she was a big part of it. Me being somebody who’s Indigenous, who comes out of Native American Studies and was trained in Indigenous research methodologies, accountability is rule number one. I wasn’t doing a research project with human subjects, I wasn’t interviewing tribal people, I wasn’t here to extract information. I was interested in the dynamics of coalition building and how the Native piece factored into this much larger story. But I relied on and made friends with Rebecca. I introduced myself because Rebecca and Angela WERE the United Coalition to Protect Panhe. So I made friends with both of them. And I took an ethic of accountability into my relationship with them, because I needed them. I needed to understand their position and how the work that they did contributed to the research. I became friends with especially Rebecca. She fed me all the documents. It was a combined effort, but Rebecca had the documents. Literally she handed everything over to me, all kinds of stuff, and it allowed me to really dig into that piece of it. It was really important for me to be transparent with them, throughout the whole process.

One of the things that came out of the Save Trestles campaign was the San Onofre Parks Foundation (SOPF). Rebecca was one of the founders of that organization, with Steve Long. You know who he is Krista, the father of Greg Long who is a very well known big wave surfer. They are a San Clemente family. Steve was a veteran lifeguard for 30 years down here. He was a State Park Ranger and lifeguard, total water man, and highly, highly respected.

Steve and a handful of other people started SOPF, which is a cooperative association, and Rebecca was an early board member. There are networks of these cooperative associations in the state parks, as the state parks have lost funding over the years to do their interpretive and educational functions. Losing funding over the years gave rise to a need for these cooperative associations that work in partnership with the state parks to provide services. They got major grant funding from another foundation, which allowed them to form the San Onofre Parks Foundation. In 2016, Rebecca decided to move to Hawaii. She bought a house, and moved with two of her sons. And she asked me if I would take her seat on the board. I felt so honored, she honored me by asking, and I felt it was the least I could do as a way to be accountable for how she worked with me and helped the research. She’s a tribal elder, older than me. Her mother was a very respected tribal elder. So for my own personal sense of accountability, the least I could do was accept. The organization sees itself as stewards of the land, and for Rebecca, this is her ancestral land. To ask me, as a non-Acjachemen person, felt huge, that she would entrust me with that responsibility.

Krista

I wonder if we could talk about your early relations to place and land, when you were small? Sometimes the conversations people are having with themselves and me . . . end up thinking back to early relations to land and outlines of them show up, later in life, in unexpected ways.

Dina

For somebody like me who is a Native person, but who was born and raised way far from my tribal community – our reservation, our homelands, are up in Washington and Canada – I knew, we knew our bigger family. But we only went there a couple of times when I was a kid.

My sisters and I were born and raised in LA, East LA. I’m the oldest of three daughters.

I’m fully an urban Indian. But I didn’t have a way of understanding that growing up. It took me going into Native American Studies to really contextualize myself.

Krista

When you were growing up in East LA, what would you say was your relation to that place, or was your family’s relation to that place? Your sisters’ or your friends’?

Dina

I don’t know. I didn’t know, I don’t know how to think about it.

My dad built us a house. He had bought a lot. He built us a house, because he was a builder, he was a plumbing contractor and then he got his contractor’s license and built us this house, on a hill. There were very few houses. We were the only one on the hill, and we were surrounded by open space. I loved walking in the hills. It was mostly dry grass. I loved it. I always felt connected to nature. And it was spiritual for me to walk the land, and to be out there by myself and connected to it.

My father was Sicilian. He’s first generation, born in the US. And my mother came to LA from Washington in the 50s and met my dad in a bar during the Indian relocation period. If she were alive, there would be so many questions I would ask her about that time.

You know the film The Exiles? A UCLA film student made the film, he followed around these Indians from the Southwest pueblos, during one 24-hour period. It was in black and white, and it’s just raw. Intense. I couldn’t watch it the first time because my mother was a barfly. My mother was full on, a severe alcoholic. She had a lot of trauma . . . There was boarding school trauma that was handed down from my grandmother, and this is how I understand myself today. My mother got scapegoated in our family because of her alcoholism. I understand it much differently now, in terms of intergenerational trauma. I know now that she also had trauma from having a child taken from her during what’s called the pre-ICWA (Indian Child Welfare Act) scoop. That’s another really long story, but I recently reconnected to three other siblings of my mom’s from before I was born, and the information the oldest one provided confirmed that that sibling was taken without her consent. I’m writing about that now in a new book.

Krista

When you were a child, you would move between East LA to see your mom’s family in Washington?

Dina

We didn’t move back and forth but we did visit a couple of times. Once when I was a baby, and I don’t remember it. Once in 1970, when I was 12 years old, and we took this epic road trip. Driving from LA to the Colville reservation is a long ass way with three rowdy kids. I don’t know how my parents did it. [laughing]. All of us in the family car.

It was a turning point in my life, I was 12. All the stuff that was happening in 1970 in LA . . . the Civil Rights Movement, Black Power and Red Power. Alcatraz, we drove through San Francisco during the Alcatraz Island occupation. Hippies were really interesting to me, and I clicked with it. The music of the time, it was a great time to be a kid in LA, to be a teenager, to be coming of age. The world was on fire with the cultural revolution. Driving through San Francisco, the hippies and the tie dye and the head shops, all the stores. I knew I was born in the wrong town! [both laugh] I was seeing the Alcatraz Occupation on the news at night . . .

Krista

And did you identify with that cause as someone Indigenous?

Dina

Oh, totally. I always knew I was an Indian and was raised being told to be proud to be Indian. It was not a luxury my mother had in her generation, but the world was changing for the better!

Krista

So your mom would talk about that?

Dina

Yeah. Oh, yeah. Plus, we are Colvilles. The Colvilles were going through a termination battle. The federal government was targeting our reservation for termination, trying to get them to give up, to move. Our termination battle lasted 20 years. It’s a case study. When people study termination, they look at the Colvilles because for 20 years, our tribe fought it and we fought each other. A lot of people thought it was a good idea.

At our dinner table, we had those conversations. Terminating the reservation was being put as a vote to the tribal membership and my mom was an enrolled tribal member. My parents would talk about should my mom vote for it or not? During the 50s and 60s, a lot of people said we should do it, because we’re modern people. They believed the hype of the federal government about releasing them from the “yoke of federal supervision.” That’s literally the language they used to sell it. Becoming “free from federal domination.” The tribes were like, yeah, we don’t want to continue to be seen as “backwards savages.” We’re modern people. And we don’t want to be saddled by the federal government.

It seemed a good idea to stand on their own. So it was tempting for them to vote for it, especially because there was money. Nobody knew exactly how much, but I distinctly remember $40,000 or $50,000 per tribal member. In the late 60s, think about how much money that was – it was a fortune. You can see why it would be appealing.

But then the tide shifted, and the elders said we should never sell our land. If we sell our land, we are no longer Colvilles, that’s literally how they put it. In the end, I think our mother voted against it. So I grew up with these conversations, knowing I was Colville. We went to the land, we hunted, we hung out with our cousins and our aunts and uncles and it was rough, because there was a lot of drinking. It was rough. The alcohol really impacted our family.

Krista

Did you have a sense of being part of the “US West?” You are growing up in LA, and loving San Francisco, knowing about what’s going on at Alcatraz, traveling to Colville lands in Washington. Anything you’d like to talk about related the US West, or how you saw that idea later?

Dina

I can’t say that I had any particular consciousness about it being “the West,” I was just within it. In all these different kinds of ways, it shows up and is expressed, manifests. The fishbowl analogy comes to mind. You’re in the middle of it, but you don’t know it. Because it’s the waters that you swim in and the air that you breathe.

Krista

What comes to mind for you?

Dina

The predominant historical narratives – pioneers, covered wagons, the Wild West, settlement.

But I think of all these other ways that the West has shaped the US, especially around the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and the 1970s, that’s a very particular way that we can talk about the West.

Krista

We’ve talked about accountability a lot here, and outside this conversation. Here you mention research ethics, friendship, how Rebecca entrusts you with documents, and then offers you a role in the San Onofre Parks Foundation. Being honored by that, and wanting to be reciprocal, you agree, you give back.

You and I have other projects we’re doing about accountabilities, the “Climates of Violence, Feminist Accountability” symposium that was in the works and then paused with COVID. And our collaborative work about surfeminism and California AB 1782, surfing as the state sport. How does feminism for you engage a conversation about accountability? Or can you think about story of how feminisms are expressed in relation to land or to place?

Dina

Yeah, you know, feminism isn’t for me like it was for you. Like you come into this very explicit feminist consciousness in the early 80s.

Krista Comer

70s [laughs]

Dina

70s. Oh! I was reading in the blog about you going to the West Coast Music Festival in the early 1980s.

Krista

Right, by the 1980s, I’m ready to go places with it. But before that, it’s happening. Yeah.

Dina

For me, I would not have known the word feminist. I could not have related to feminism. But I would learn later from other Colville women, they would tell me, “Colville women were always in charge.” Colville women, including my mother, were never subservient to men. And even my mother, who was so crippled by her own trauma, would never succumb to my Sicilian father’s attempts to dominate her. She modeled that for me, I understand that now. You could say that’s a lived Indigenous feminism for Colville women. But once I look back on it, I was being it.

Krista

This looser sense is what our conversations have been teasing out. I don’t know that I used that term either. But I know that I was oriented in that direction. And I wasn’t taking no for an answer.

Dina

Right. That’s how I was – not taking no for an answer. Here is a story: the way that showed up for me was in high school, and I was a majorette. I grew up being a majorette from the time I was 7. I was a really good baton twirler. I always had a dream that I was going to be the majorette for my high school. So I get there, and I’m really good. But our school had never had a majorette. I tried to find out how could I be that? I go to the drill team, well known in LA for how good it was. The drill team instructor was like, No, no, no, no, no, I don’t want a three ring circus out there in the halftime shows on the football field. Shut me down.

I was so mad. But I’m not taking no for an answer. And who does that? Like who shuts down a kid’s dream like that?

I went to the school principal, Miss Avant. I told her what Miss Most [the drill team instructor] had said. The principal could appreciate it because she had been a majorette.

She was very cool about it, diplomatic. She says to go see Mr. Rinaldo, the band director. See what he says. So Mr. Rinaldo . . . it’s his jazz band – Eagle Rock High School was known for its jazz band. It was the best high school jazz band in the state. Mr. Rinaldo, he hated marching band, he hated that he had to do marching band. And he said: I don’t care what you do, just don’t get me in trouble with Miss Most. In other words, me being the majorette was part of the marching band under Mr. Rinaldo’s jurisdiction, not the drill team director’s. It was a way for me to subvert unjust authority.

I had to follow certain parameters after that, but I made it happen. I was the high school majorette for three years. I’m not gonna let somebody freaking shut me down, and accept no for an answer. And that was the kind sensibility that I brought into surfing, maybe eight years later.

And my mother, we come from a tribal culture that was gender equitable. Most Native cultures are matrilineal and if not, at least matriarchal. Women have power. Our tribe was that way, even though my mother never would have said it in those terms. And she was so dysfunctional. She caught so much dysfunction, but she embodied the power. She fought with our father. All the years I was growing up, he was the quintessential patriarchal Sicilian father, saying: You’re going to get married and have kids and if you want a job, be a secretary, a hairdresser, because that’s what the women in that family did.

I was like, no fucking way. And my mom always said you can be whatever you want to be, you do what you want to do. You be an individual, you figure out who you are. That’s how she raised us and she had to fight our father about it. This clash of cultures within our family is really how I understand it now. She would not capitulate to him. She had to fight with him a lot and the message came through loud and clear for me and my sisters. My younger sister became the first in our high school to be the on the guys’ gymnastics team. Nothing like that had happened before. She was so good, too good for the girls’ team, so they let her be on the guys’ team. She has been breaking barriers as an athlete all her life.

Krista

This is the one that also surfs?

Dina

Right. She surfs, and races cars. She’s a level three ski instructor. She’s radical. She’s a radical jock, jockette. Our other sister is an amazing musician. And an athlete. We all three of us did things none of the other women in our family were doing. We didn’t recognize limits.

By 1980 when I moved to Hawaii . . .

Krista

Pipeline seemed possible?

Dina

Yeah. Women don’t surf Pipeline, but why not? Why can’t I? Like who’s gonna say no?

Krista

But I assume some people said no.

Dina

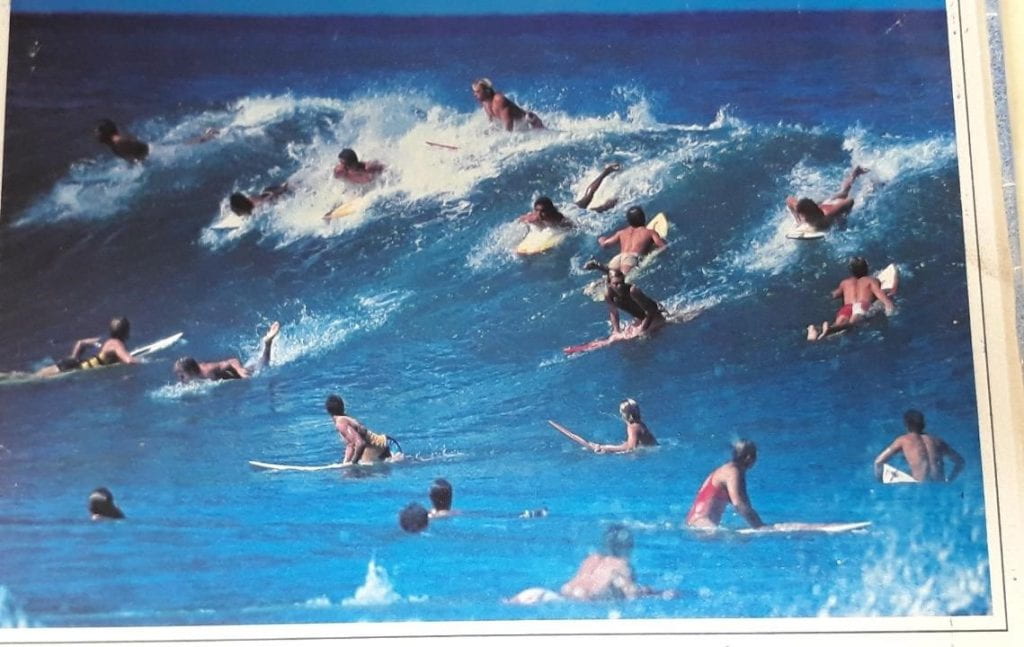

Well, the guys didn’t like it, but more to the point, they didn’t take me seriously. And, it’s testosterone hell, a place like that. And I will show you this photo – it’s the only time I was in Surfer Magazine, ‘81, or ‘82. The back cover. They took a photograph of the crowd, the pipeline littered with people. I’m the only girl in the crowd, documentary evidence that it’s true. Probably 30 people in the frame, and me, the only girl with all the guys scrapping for waves. And I’m just watching them go by-

That’s Dina in the red swimsuit, the only girl at Pipeline. Surfer Magazine back cover, 1981 or 1982.

Krista

Sitting on the shoulder? Hoping? [laughs] Trying to keep your wits about you?

Dina

Pretty much, pretty much.

Krista

Wow!! Fast forwarding to now, how would you express feminist thought? You and I have had many conversations about this over some years. I’m not looking for a set thing. But there is being a “strong woman,” as an individual, then there’s having a feminist framework to understand structures or relationships, one might feed the other, but they aren’t the same thing. You can’t stage an argument by being a strong woman. You can if you’re out surfing, but in terms of a way to think about a liberation project?

Dina

Yeah. It’s about reclaiming women’s power, as a Native person, on a cultural level, like being told that Colville women have always been in charge which has stuck with me so much. Despite the way it looks, the way that it’s come to look in Indian country during the Red Power movement when the men had the mic and, and there was a lot of abuse in in those movements-

We all know that American Indian men have internalized a lot of patriarchal behavior, but Colville women have always resisted that. For me, hearing that was so empowering. My mother was not empowered, at least outwardly, but when I really think about it her whole life was about resisting colonial-patriarchal abuse. Though she raised us to be individuals, she was so dysfunctional, and there was just so much trauma. It’s so interesting how your perspective about the things that shaped your life can change so much as you mature.

To get to the framework of feminism as a project, like an intellectual project, is useful because it gives us a common language, that’s what’s so attractive.

Krista Comer

Right. And ideally, a community, a relational project, you know, not an abstract kind of idea.

Dina

Yeah that common language. I never took a class in feminism, ever. The classes were there, especially in grad school, but for whatever reason, it didn’t compel me. It wasn’t until I was out of school that I became more aware of Indigenous feminist thought.

This common language allows us as women to talk to each other across difference. And that’s why it’s so important to understand various kinds of feminist projects, you know, white feminism, and black feminism and queer feminism, Indigenous feminism . . . the ways feminisms show up in these particularities. Because they’re different. You felt like your identity was really as a feminist, right? That was core to your identity. My core identity was being Indigenous. I had to figure out who I was in the context of that, before I could get to who I was as a woman. If that makes sense.

Krista

I hear a lot of women of color say that and a lot of Indigenous women say that. Yeah.

For me, being a girl, a woman, was the core identity, I would not have called myself a white girl, I was a girl, and my feminism in those days was some kind of attitude or fury about sexual violence. Or the need for economic autonomy. The idea of “equal pay” was not in my mind, I was not connected to organized groups like NOW. It was more about: how should I understand this thing that happens in the world, that’s happening to me and my friends, the weird behavior of boys and young men? At the time there were no terms like “date rape” or “harassment” or “stalking,” or predatory older guys, but there some behavior seemed profoundly weird and off. And economic autonomy, not equal pay, but I would have called it independence. Otherwise, how to control your life? “Reproductive freedom” was not in my mind. I cared about economic survival without being attached to my parents or a man. Without having anyone pay your way. I would not accept people paying my way.

I was a very outspoken girl as a teenager . . . none of my friends felt so strongly about “not taking no for an answer” and I didn’t even know where it came from. I did not know the language of feminist yet, I just knew I was going to speak my mind and fight back. That was what caused the most trouble and why the boys got so mad — I smoked and drank and all that, but the trouble really was the fact I had a mind and didn’t hide it. That’s what I think today. I was always challenging stuff — parents, boys, teachers.

Dina

I like this Living West project as an interactive way of talking about feminism that …keeps it alive for regular women. So it doesn’t get bogged down, because if you’re not studying feminism, in an academic way, it seems that either you are a feminist or you’re anti-feminist. In the world, “feminists” are a dirty word for a lot of people.

Krista

Or feminism is “equal pay.” Getting a piece of the pie, Sheryl Sandberg and Leaning In and being able show up for “careers” and balance it all. That’s a feminist.

Dina

Yeah, it’s a narrow way of seeing things.

I think humanity is always trying to give birth to something new. And it’s revolutionary because life as we know it in a Eurocentric society is steeped in oppression, all kinds of oppression, like, that’s what patriarchal colonialism does. As we try to give birth to something that transcends these multiple oppressions, it’s gonna be women that are going to change the world, women and Indigenous people, and other people of color, that’s where it has to go. That’s what it means to shed or transcend oppressions. To be a woman with a public platform is no small thing. And I take pride in that. From not being willing to accept no for an answer and being a majorette to just calling it like it is, to talking about colonialism on the pages of Sierra Magazine or other non-Indigenous publications.

Krista

Yeah, those recent pieces of yours are great. They hit hard. They “school” audiences. Whether people can tolerate it’s a different matter.

Dina

This is what I do, though, in Zoom rooms and classrooms and big rooms of scientists and lawyers and conservationists. I tend to be pretty uncensored, and I’m constantly surprised about not having a lot of pushback. People are ready to hear.